Send In The Drones

In The Ring - April 22nd, 2022

“In times of change, learners inherit the earth; while the learned find themselves beautifully equipped to deal with a world that no longer exists.” -Eric Hoffer

This week’s Haymaker examines the inarguable and historical significance of advanced (or advancing) technology in warfare. The obvious case in point at present is on display in Ukraine’s efforts to stave off Russia’s incursion. As this is a financially focused newsletter, today’s note examines the investment implications of this immense geopolitical shift, the realities of tech-heavy defense spending, and the tendency to think in big, pricey terms when new weapons systems are on the table. As you will read, one of the main long-term repercussions might be on the U.S. dollar.

I would also like to point out that this article reflects a fruitful group effort. Given the military history, tactical themes, and large-scale martial topics I knew I wanted to cover, I decided to invite the direct aid of two sources who have each spent time in uniform and also possess academic knowledge of warfare. (The only uniform the Haymaker ever wore was in the Cub Scouts!) Louis-Vincent Gave, Evergreen GaveKal Director and a good friend of mine, along with my longtime editorial consultant and creative contributor, Mark Joseph Mongilutz, assisted in the authoring of this piece. The result of our combined work is an analysis that spans from age-old battles to modern techno-strategic realities and circumstances, all presented from a macro-financial angle.

Let’s tighten the gloves.

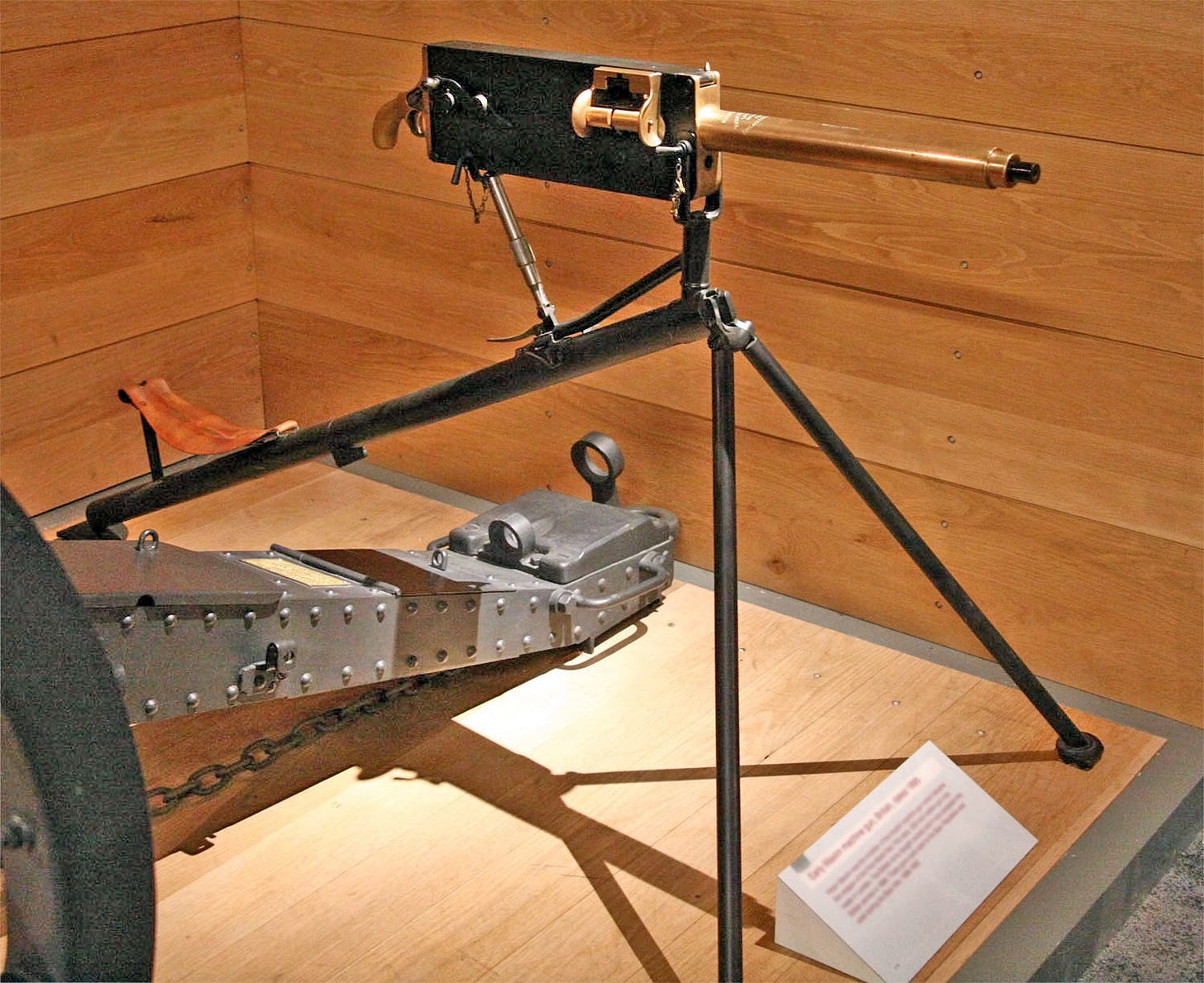

In October 1893, some 6,000 highly disciplined warriors of King Lobengula’s Ndebele army launched a night-time attack on a camp occupied by 700 British South Africa Company (BSAC) police near the Shangani River in what is now Zimbabwe. It was a massacre. The BSAC “police” killed more than 1,500 Ndebele for the loss of just four of their own men. A week later, they did it again, killing some 3,000 Ndebele warriors for just one British policeman dead. These one-sided victories were not won by courage or superior discipline, but because the British were armed with five machine guns and the Ndebele had none. As Hilaire Belloc wrote in The Modern Traveller: “Whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun, and they have not”.

(Maxim Gun - Source: Max Smith, Wikimedia Commons)

The technological superiority of the machine gun allowed Britain, and, in time, France, Germany and Belgium, to subjugate almost all of Africa, even though vastly outnumbered by the Zulu, Dervish, Herero, Ndebele, Masai and even Boer forces they opposed. All were rendered helpless by the machine gun’s phenomenal firepower. I revisit this ancient history to illustrate how military technology is a lynchpin of the geopolitical balance.

Dominance of military technology is also a key factor underpinning the strength and resilience of a reserve currency. Today, one of the main reasons why Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and others keep so much of their reserves in U.S. dollars is that the U.S. is widely regarded as being a generation (if not more) ahead of the competition in the design and production of smart bombs, anti-missile systems, fighter jets and naval frigates. The superiority of U.S. weaponry has been one of the principal factors underpinning the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. However, recent events raise important questions about whether the US can retain said superiority.

In September 2019, drones allegedly deployed by Yemeni Houthi forces took out the Saudi Aramco oil processing facilities at Abqaiq.

Between late September and early November 2020, Armenia and Azerbaijan fought a war over the Nagorno-Karabakh region. The conflict ended in near-total victory for the Azeris. This result stunned the military world. Observers had assumed that Armenia, with a bigger army, larger air force, more up-to-date anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems, and a history of Russian support, would easily triumph. But all of Armenia’s expensively acquired military “advantages” were quickly taken out in the early days of the fighting by Azerbaijan using Turkish-made drones costing roughly U.S.$1mn each.

On March 6, 2021, Houthi drones again attacked Saudi Arabia, aiming to take out the oil storage facility at Ras Tanura (although this time they inflicted only light damage).

In December 2021, the Ethiopian government tipped the balance in a domestic civil war that had been going pretty poorly for government forces thanks to Turkish made drones (https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/20/world/africa/drones-ethiopia-war-turkey-emirates.html)

On January 17th, 2022, Houthi drones hit oil facilities in the UAE for the first time (https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/2/3/timeline-uae-drone-missile-attacks-houthis-yemen)

Now, imagine being Saudi Arabia (or the UAE). Over the years you have spent tens, if not hundreds, of billions of U.S. dollars purchasing anti-missile and anti-aircraft systems from the U.S. Now, you see relatively cheap drones penetrating these defense systems like the proverbial hot knife through butter. This must be frustrating. What is the point of spending up to U.S.$340 million (mn) on an F-35C (and an additional U.S.$2mn on pilot training), or U.S.$200mn on an anti-aircraft system, if these can be taken out by drones at a fraction of the cost?

The reason I highlight this is of course the impressive resilience of the Ukrainian army in the face of the Russian onslaught. Indeed, when the Russian troops walked into Ukraine, consensus opinion was that the Ukrainian forces would not be able to withstand the Russian military juggernaut. And while it is always hard to know what is going on in specific battlefields amidst the fog of war, it would seem the Ukrainian invasion has proven more challenging for Russian troops than anticipated by the Kremlin. Destroyed tanks, sunk battleships, a Russian air force that is struggling to assert control over the Russian skies… The war in Ukraine is likely proving much costlier on Russian troops than Vladimir Putin had anticipated. Could this be because Putin failed to incorporate the impact of drones in his military outlook?

It is perhaps premature to jump to that conclusion. But judging from afar, it would seem inexpensive Turkish drones have helped level the warring field in the Russia/Ukraine, David vs. Goliath confrontation, the biggest and bloodiest on European soil since WWII.

This would explain why, included in the military assistance package for Ukraine that President Biden announced this month, one could find 100 Switchblade drones. These are surprisingly low-cost yet highly effective. The Switchblade 300 reportedly carries a price tag as low as $6000. They are essentially “Kamikaze drones”.

(Switchblade 300 - Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Apparently, these drones fly far faster than the Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones that have been utilized to such devastating effect by the Ukrainian, and Azeri military forces. Accordingly, Switchblades should be able to evade the air defense Russia has been maintaining (sort of) above its land-based troops.

Previously, the U.S. military deployed Switchblades sparingly in Afghanistan, so there is no large body of evidence as to how well these will perform in combat conditions. But prior to this shipment to Ukraine, only the UK was allowed to purchase Switchblades. This would imply that, as far as the Pentagon is concerned, this is a highly valued and potent weapon.

Per Four-star General David Petraeus, former CIA director and the leader of America’s campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan, in a recent interview on the war in Ukraine with the acclaimed historian Niall Ferguson:

“I’ll mention one item in particular: the Switchblade drone. It’s a loitering munition that takes a one-way trip. The light version can loiter for 15 to 20 minutes. Heavy version, 30 to 40 minutes with a range of at least 40 km. The operator selects a target, it locks on and it follows. Then it strikes when the operator gives that order. This is extraordinarily effective because you can’t hear it on the ground. The first time the enemy knows it’s there is when it blows up. If we can get enough of those into Ukraine, they could be a true game-changer. I don’t know if we can, however.”

(Bayraktar TB2 - Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Now needless to say, with this discussion on weapons efficacy, we are veering far from our area of predilection, namely financial markets. So let us bring back the discussion to why drones may matter for financial markets.

Firstly, if drones, like the Maxim machine gun of yore, are set to revolutionize warfare, then given the growing ease and collapsing cost of drone production, does it still make sense to invest in tanks, airplanes, anti-aircraft and anti-missile systems? And if it does not, what does this mean for the value of the large, listed defense contractors? Historically, buying these companies after a big rally in oil made sense, if only because so much of the world’s high-end weapon consumption occurs in the Middle East. But in the world of tomorrow, will Middle Eastern oil kingdoms line up to buy billion-dollar systems from the Raytheons, Boeings and Lockheeds of this world, if their systems prove powerless to stop drones?

Secondly, and since we are talking of Middle Eastern regimes, the deal that prevailed in the Middle East over the past five decades has been that oil always remained priced in U.S.$, and that regimes like Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, or the UAE could then use these U.S.$ to buy U.S.-made weapons. With this bargain, the U.S. implicitly guaranteed the safety of most of the Middle-Eastern regimes. Now, interestingly, in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE failed to condemn Russia. Worse yet, Saudi Arabia let it be known that they may start to accept RMB, China’s currency, for their oil. Which perhaps makes sense if Saudi Arabia feels it no longer needs $340 million F-35s but instead more $750,000 Turkish-made drones?

Thirdly, if, as both the Azeri-Armenia and the Ukraine-Russia wars seem to suggest, drones have now radically leveled the playing field in warfare; this is a profound development with a multitude of implications. Does this undermine the long-held superiority of vastly expensive armament systems, thus tilting the balance in favor of much cheaper and much more widely available weapons? If so, does this mean yet another support pillar of the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status is crumbling in front of our eyes? After all, in a world where military might is no longer the monopoly of one or two superpowers, do we de-facto move into a multi-polar world? One in which there is no reason for trade between Indonesia and Malaysia to be settled in U.S. dollars, as it can now be settled in their own currencies? Similarly, shouldn’t trade between China and South Korea be settled in renminbi and Korean won?

However, before we give the U.S. dollar and American military domination the last rites, we should consider a few historical realities. There has always been the tendency of military tacticians to fight the last war. Nowhere was this more vividly — and tragically – illustrated than in Louis’s home country of France. After WWI, the French high command spent vast sums building the impregnable Maginot Line in a desperate attempt to avoid a repeat of the “War To End All Wars” trench warfare nightmare. Hitler simply drove his tanks around it, through the allegedly impenetrable Ardennes Forest. Fortunately, America has proven more adaptable over the years which is perhaps why, more often than not, it’s been on the winning side.

Drone tactics are unquestionably a radically different form of warfare, and they are evolving. Thus, it’s premature to come to definitive conclusions as to how dominant they’ll be in the long run. However, while reaching parity with ultra-sophisticated weapons like, say, the F-35, is out of reach for most nations, doing so in the unmanned-aviation vehicle (UAV) arena is certainly possible, even for the militaries of nation states less affluent but more aggressive than the U.S. In other words, it is possible for a country like Russia. Thus far, it hasn’t been impressive on the drone front — or most fronts in the Ukraine conflict, for that matter — but it’s early innings.

As has been explored and covered by military experts, defense industry professionals, and armchair observers, drone warfare on a large scale might be the first step towards reduced manpower presences in warzones. But there is reason to be skeptical, as such thinking also accompanied the emergence of manned aircraft in the early- to mid-20th century. As many infantrymen and tank crews can attest, the need for ground-based units hardly subsided. Still, it's worth asking the question: Where will the UAV age lead? (For a sobering look at the psychological trauma suffered by drone operators, please access this recent New York Times article.)

The West is understandably pulling for Ukraine – certainly for its people, warfighters and refugees alike – and every sign of victory, on any scale, is amplified by intense media coverage. This is clearly happening in response to the lethality of drone technology. It’s certainly possible, per General Petraeus, that if the West provides Ukraine with enough drones, they will prove to be decisive. However, there is the alternate scenario in which they contribute to a short-term stalemate of sorts, one where a conservative Russian response creates fewer openings for UAV strikes but that keeps either side from gaining clear advantage.

It's hardly insightful, but nonetheless accurate, to point out the long history of innovative attacks running rampant until they collide with a suitable defense, which need not even be perfect to blunt the advantage of a strong weapons system. In this regard, the future of military confrontations may increasingly be between offensive and defensive drones. Much of this note has covered the challenges to U.S. military hegemony, but when it comes to high-tech weaponry America still is the standard to match. It’s possible in the not-too-distant future that whichever countries possess the best drone capabilities will be formidable foes, at least in conventional warfare, even for the US.

Accordingly, it’s certainly feasible that drones might well be the modern-day equivalent of aircraft carriers in WWII that made traditional naval warships, if not obsolete, at least highly vulnerable. Two early Pacific battles reflected the new reality. The Battle of the Coral Sea in May of 1942, generally considered by historians to have been a draw, was the first naval engagement ever fought where the opposing fleets never made visual contact with each other. Carrier-based aircraft basically drove the hostilities. The far more consequential Battle of Midway, mere weeks later, proved the essential nature of carriers. The Japanese Imperial Navy was ambushed northwest of Hawaii and lost most of its aircraft carriers almost instantly. It would be on the defensive for the rest of WWII.

With hindsight, the Battle of Midway was the start of the U.S. rule over the world’s high seas. In short order, this led to American dominance of global trade. But as warfare changes in front of our very eyes, is this dominance of oceans, and of any future battlefield, guaranteed to last? Investors need to consider the uncomfortable possibility that it might not.

An Ask Of Our Subscribers

Haymaker has a lot of rounds ahead in what would be a very tough fight without you in our corner. You can back us up by tapping the heart and, even better (though we appreciate both), weighing in with a comment. If you haven’t done so, look for the intuitive shapes, and keep your favorite financial pugilist punching with all his might.

Okay, that’s the bell. We’re back at it.

Special note: We are moving our market commentary and action item communication, Making Hay, to a Monday publication date. The next of these will be published on April 25th.

I enjoy your financial essays a lot and this article is interesting from technical and historical point of view. But bragging about support for bloody Kiev regime is frankly disgusting. The main military advantage of Ukrainian army is not just a complete disregard for civilian lives(and it's not even civilian lives in some foreign countries, but own citizens), but actively utilizing civilians presence. A widely adopted tactic to hide heavy military equipment in residential areas, near schools and hospitals to prevent return fire makes Russian troops progress indeed difficult. Since 2014 Ukraine military rotated majority of active servicemen through ATO zone in order to determine and foster insensitivity to human lives. Apparently not everyone can fire on innocent people. So selection process was necessary.

So drones or not, Ukrainian military will be decimated. It's just a right thing to do. Russians should be (and I think they do) targeting western weapon cargos right on the borders for ground deliveries or in the air/on airfields, before they reach the destination. Although lots of that weaponry ends up in the hands of Donbass fighters and they surely use them well.

I do understand that you have to be on the "correct" side politically, otherwise the authorities will crush your business, but still a thumb down for this one.

I greatly enjoy everything I read from Evergreen and Gavekal.