“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” -George Santayana

"We are in the business of making mistakes. The only difference between the winners and the losers is that the winners make small mistakes, while the losers make big mistakes.” -Ned Davis

Momentum vs History

Partially due to the fact that I’m still rewriting one of the most important chapters of my book, Bubble 3.0 (sub-title: Who Blew It And How To Protect Yourself When It Blows Apart), we are running another Guest Haymaker. However, that’s definitely not the only reason.

For one thing, we like the idea of occasionally sharing some of the more intriguing articles we come across in the course of our extensive reading. The fact that the Guest Haymaker we ran two weeks ago received the highest number of views we’ve ever had — nearly 24,000 vs our more normal ~17,000 — was encouraging in that regard. Perhaps it’s a testament to the far greater appeal of Charles Gave, who wrote that piece, than of yours truly!

This week we’re running a missive from someone I’ve only recently started following, fellow Substack scribe Jim Colquitt. Despite my short history of tracking him, in this particular post he’s homing in on an indicator I once regularly followed for many years. My first exposure to it was thanks to the illustrious Ned Davis. His peer, Barry Ritholtz is on record that, “Ned Davis may be the single most highly rated Technical Analyst working today.”

For years, I was a client of his firm, the eponymous Ned Davis Research. However, a number of years ago, Ned sold out to a much larger firm and two of my favorite analysts of his — Vincent Deluard and Warren Pies — eventually left. As a result, I let my subscription lapse, but I’ve never forgotten that one of Ned’s favorite indicators was the same one that is the subject of this Guest Haymaker.

Ned was adamant that this was among the most accurate forecasters of long-term stock market returns he’d ever encountered. It also has the advantage of being both simple and logical. Drum roll, please: his magic indicator was, and is, the average investors’ percentage allocation to stocks. In an era of constant encroachment into the investment world by computers, algos and, now, AI, it’s nice to have a proven guidance system that is so utterly human. (A couple of ironies: Ned was one of the early incorporators of high-powered computers into his investment process; second, the track record of the original AI-driven ETF has been unimpressive, with returns barely above half of the S&P since its 2017 inception.)

It shouldn’t shock anyone that when investors are in aggregate heavily exposed to stocks, the pool of future buyers is limited. Thus, it’s rational that equities would have a strong tendency to underperform in those circumstances. And that’s exactly what history tells us, as you’ll see in his first chart.* It’s this initial image that is the most important for you to peruse, by the way.

Please note that the 10-year forward return line, in yellow, with percentages on the right axis, is inverted. As this chart illustrates, when investors are highly committed to stocks, the returns a decade out are far below average. For example, when the highest stock exposure on record was hit in 2000, the returns over the next 10 years were abysmal… as in, actually negative. Conversely, when the average investor allocation to stocks was very low in 2009, the gains over the next decade were stellar — roughly 13% annual returns.

You can see that same pattern from the bottom of the vicious mid-70s bear market to the beginning of the 1990s when stocks were chronically unpopular and under-owned. Forward 10-year returns were largely in the double-digits (and never close to negative) in those glory days for contrarian investors.

Conversely, when investor allocations to stocks were near a post-WWII peak, during the Nifty Fifty era of the early 1970s, returns were also negative over the next decade, especially after inflation. The heavy concentration into a limited number of high-flying, and high-multiple, stocks was eerily similar to present conditions, including that there had been a tech stock bust just prior to that follow-on bubble.

But, of course, what you really care about is the message this indicator is sending today. You’ll immediately notice that in 2021 the average investor allocation basically made a double-top with 2000. (The latter instance, by the way, was the peak of the greatest equity bubble in American history, exceeding even 1929. In Bubble 3.0, I argue 2001 was yet more insane, at least with lottery tickets like profitless tech stocks, worthless cryptos and the meme playthings of the Robinhood/Reddit mob.)

Jim is making a number of other critical points, but I don’t want to front-run him any more than I already have. However, I would direct you to his charts/section on the S&P 500’s “absolute value” where he suggests that in this period of such persistent investor euphoria we will see big selloffs and powerful snap-back rallies. Of course, that’s exactly what we’ve seen thus far in 2022 and 2023. Accordingly, I think he’s totally on-target with his assertions in here. You will read, though, that he avoids making any near-term forecasts. Based on how flighty and fickle investor sentiment is these days, that’s a wise approach.

For those of you who are willing to consider history and position for the next seven years, versus the next seven weeks, this might be one of the more important articles you read. In my view, this is particularly true given that I believe we are in the midst of an echo bubble, the offspring of the grand daddy of them all. The message here is that because of this latest intoxicating rally, at least by a handful of massive tech stocks, investors are once again way out over their skis with equities. To ignore this has the high likelihood, based on lengthy market history, of amounting to a very big — and costly — mistake.

-David “The Haymaker” Hay

P.S. We understand not every subscriber calls these United States their home, but we nevertheless wish you all a celebratory and happy Independence Day.

*If any of the charts below seem too small to make out, simply click on them to expand.

To learn more about Evergreen Gavekal, where the Haymaker himself serves as Co-CIO, click below.

Haymaker Note: The below content from Mr. Colquitt is what we originally intended to reprint. It replaces a different article which ran in the first iteration of this edition. We regret the error and thank you for your understanding.

Sneak Peak: How does a -0.07% annualized return for the next 10 years for the S&P 500 Index sound?

JIM COLQUITT | JUN 21, 2023

It is time for the quarterly update of my favorite chart, the “Average Investor Allocation to Equities” chart.

This is one of the most important charts you will see as it is extremely helpful in providing a glimpse into what to expect over the next decade for US equity prices and other major asset classes.

Let’s start with a definition.

The blue line in the following chart shows the “Average Investor Allocation to Equities”. As the name would imply, this line shows how much (i.e., what percentage) of the average investor’s portfolio is allocated to equities at any given time as opposed to other asset classes (i.e., fixed income, commodities, cash, etc.) This line maps to the left-hand scale of the chart.

The yellow line in the following chart shows the “10-Year Forward Annualized Price Return” of the S&P 500 Index. This is telling us what the 10-year forward return was for the S&P 500 Index from the corresponding point on the blue line. This line maps to the right-hand scale of the chart and the values have been inverted to better show the relationship between the two metrics.

How do we interpret this chart?

Very simply, the higher the blue line (i.e., the “Average Investor Allocation to Equities”), the lower the subsequent 10-year return for the S&P 500 Index and vice versa.

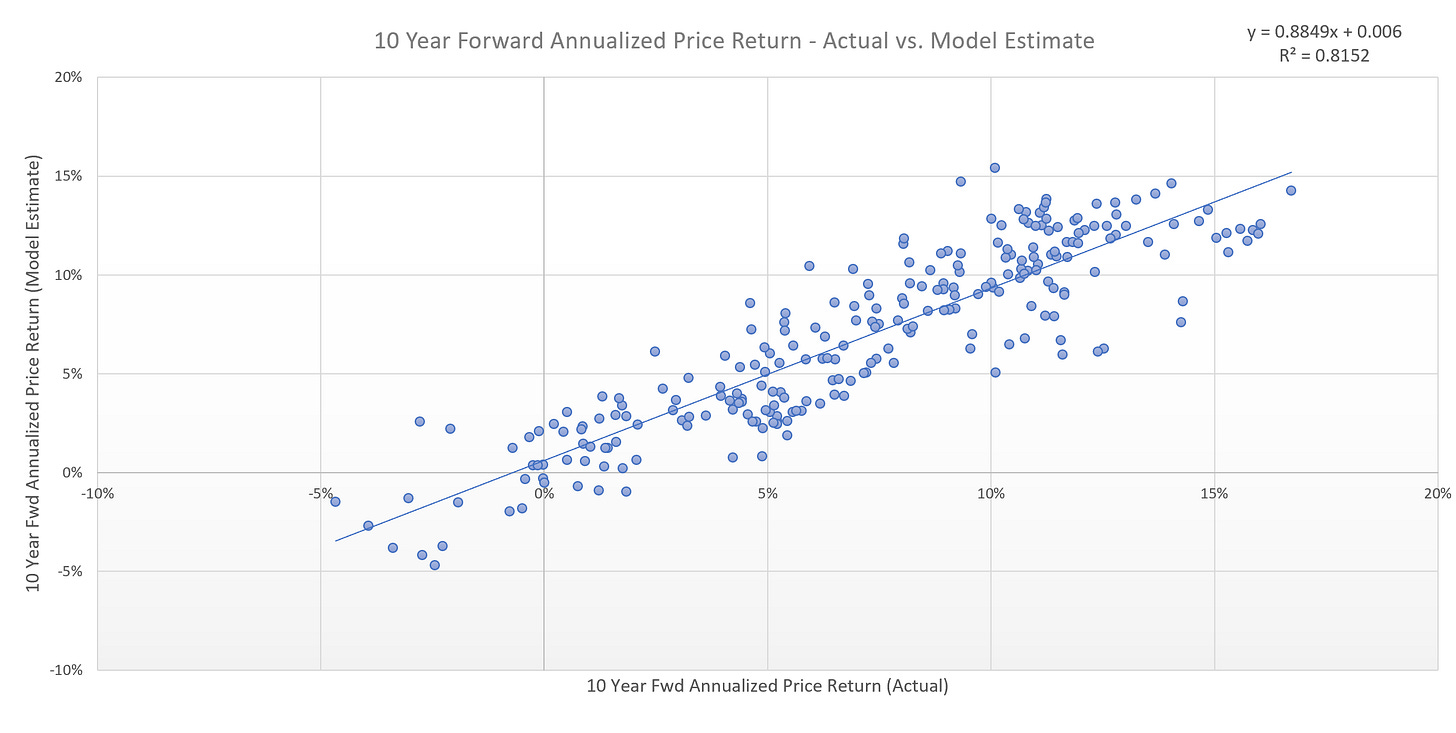

Given the tightness of fit for these two lines (note the correlation figure in the top left-hand corner of the chart), I have created a model to project forward returns for the S&P 500 Index (see chart below).

The current “Average Investor Allocation to Equities” figure is 46.23% as of March 31, 2023 (our most recent update). This corresponds to a projected annualized return of -0.07% over the next 10 years for the S&P 500 Index.

It is important to remind readers that this does not mean that we should expect a return of approximately -0.07% every year for the next 10 years. Instead, what it means is that over the next decade, we will likely see a market that has very dramatic sell-offs followed by very dramatic rallies which will net out to effectively no return over the next 10 years.

Digging deeper.

The following chart is the same as the first chart in this article but I have added a few elements to it.

I have segmented the chart into three sections. Each section represents a full cycle of the “Average Investor Allocation to Equities” cycle. Note that the first two cycles took 29 years and 27 years, respectively. I used an average of the first two cycles to suggest that this current cycle may take 28 years in total. For the record, it could be longer or shorter, this is simply an educated guess based on the last two cycles.

The key takeaway here is not the length of the cycle but to understand where you are in the cycle. The first half (“green arrows”) of the cycle is typically associated with rising equity prices as the equity allocation in an investor’s portfolio steadily increases. Alternatively, the second half (“red arrows”) is typically associated with lower equity prices and increased volatility as the equity allocation in an investor’s portfolio steadily declines.

When we translate the above logic/metrics to the S&P 500 Index, we get the following chart. The “green arrows” below are the first half of the cycle, and the “red arrows” are the second half of the cycle.

At best, during the “red arrow” portions of the cycle, the S&P 500 Index moves sideways to lower, but note the dramatic swings within the period.

Here is a zoomed-in image of the “red arrow” period from 1968 - 1982. Note the dramatic swings in prices and the fact that we had four recessions (grey vertical bars) during this period.

Here is a zoomed-in image of the “red arrow” period from 2000 - 2009. Again, note the dramatic swings in prices and that we had two recessions during this period.

Where does this leave us today?

We are currently in the back half or “red arrow” portion of the current cycle. As noted above, this would suggest that we should expect the following market/economic conditions over the next decade: 1) increased market volatility, 2) sideways to lower returns for the S&P 500 Index, and 3) a recession or two.

To get a bit more specific with regard to the S&P 500 Index and where it may be headed, I have created a “fair value” model. Here are the model results plotted against actual results. While no model is perfect, an R-Squared value of 0.81 is pretty decent.

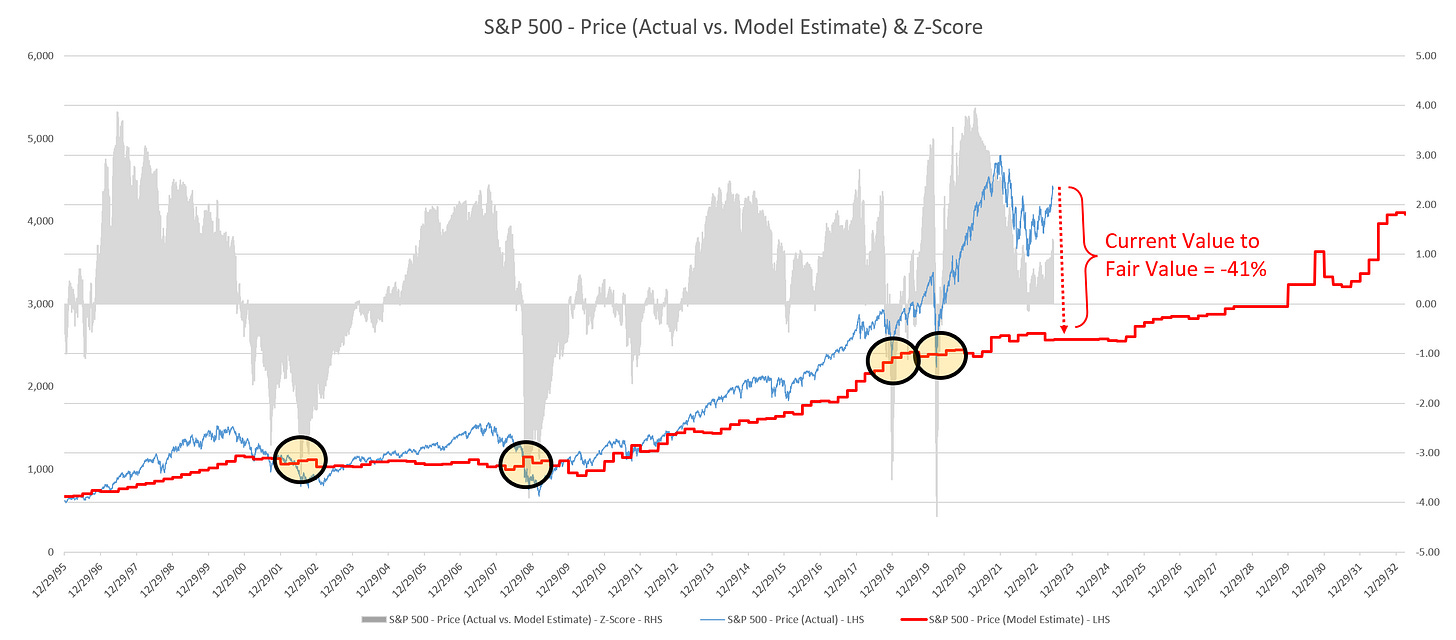

When we take the results of the model and plot them against the S&P 500 Index and into the future, we get the following chart.

The model suggests that the fair value for the S&P 500 Index is currently 2,567. Compare this figure to the current value for the S&P 500 Index (4,365) and this would suggest that the S&P 500 Index would need to decline by approximately -41% to reach fair value.

While this may seem like a large decline (and it is), it’s not unprecedented. Note the four highlighted areas on the chart (yellow circles). These circles represent the point at which the S&P 500 Index reached its fair value after having been severely extended like we are today.

In two of these instances, the S&P 500 Index would go on to decline well through the fair value line. In the other two instances, the decline stopped at the fair value line.

The average peak-to-trough decline in these four episodes was -39% with two of these episodes registering declines greater than -50%.

How will we know when we’ve reached the market bottom?

Unfortunately, no one rings a bell and says that the selling is over and that’s it time to get back to buying. However, we can make a couple observations.

First, in each of the four highlighted scenarios outlined above, the market fell to or through the fair value line. With that said, we should expect the S&P 500 Index to decline to its fair value line at some point in this cycle.

Second, in all four instances, the market bottom was not reached until our Z-score metric (grey histogram in the chart) reached a value between -3.0 to -4.0. In the chart below, I have highlighted with red circles when this occurred. As a point of reference, the current Z-score is +1.23 so we have a ways to go.

What does this mean for other asset classes?

The above framework suggests that we should expect lower equity values as we move forward over the next decade. It also suggests that we are likely to have a recession or two. While we cannot forecast with any certainty when these recessions may start or their magnitude or duration, we can look at what has happened in previous recessions to get a sense what could happen going forward.

Recessions are generally associated with a decline in gross domestic product (GDP) which signifies reduced demand for goods and services in the US economy. This tends to lead to lower equity prices as well as lower prices for various commodities, especially those on which the economy runs, namely crude oil and gasoline.

As visible in the charts below, economy supported commodities like crude oil and gasoline tend to run up in value just before a recession, only to be followed by a fairly dramatic move lower once economic demand declines.

Are the peaks of last year in crude oil and gasoline telling us that we’re already in a recession or should we expect one last rally before a recession sets in?

Crude Oil

Gasoline

Alternatively, as I made the case in What Should We Expect After the FOMC Pauses Next Week?, once the recession sets in (or is perceived to be coming in short-order), the FOMC will attempt stimulate the economy by reducing rates and likely reinstating quantitative easing. In doing so, US Treasury yields will fall (prices will rise) as evidenced in the following chart of the US 10 Year Treasury bond.

Is it time to buy US Treasuries in advance of said recession?

Summary

While I hate to be the bearer of bad news by suggesting that US equities may have close to 0% return over the next decade, my goal is to arm you with the knowledge needed to profit from these potential outcomes.

Let me be clear, I am not suggesting that a recession is imminent or that we should expect equities to decline by -41% in the short-term; however, I am suggesting that there is a high probability that these things will happen over the medium-term given what history has shown us. The timing is always the hard part.

Recessions and down markets can be an emotional roller coaster for many people. That is why I believe it is always best to develop a systematic process to remove emotions from the decision making process. In doing so, you dramatically increase your chances of making better decisions and having better results in the portion of the cycle that is often more difficult.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material has been distributed solely for informational and educational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or to participate in any trading strategy. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, adequacy, or completeness cannot be guaranteed, and David Hay makes no representation as to its accuracy, adequacy, or completeness.

The information herein is based on David Hay’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions regarding future events based on information available to David Hay on a formal and informal basis as of the date of this publication. The material may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that any opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary discussed herein will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. Actual experience may not reflect all of these opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary.

David Hay shall have no responsibility for: (i) determining that any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein is suitable for any particular reader; (ii) monitoring whether any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein continues to be suitable for any reader; or (iii) tailoring any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein to any particular reader’s investment objectives, guidelines, or restrictions. Receipt of this material does not, by itself, imply that David Hay has an advisory agreement, oral or otherwise, with any reader.

David Hay serves on the Investment Committee in his capacity as Co-Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal (“Evergreen”), registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The registration of Evergreen in no way implies a certain level of skill or expertise or that the SEC has endorsed the firm or David Hay. Investment decisions for Evergreen clients are made by the Evergreen Investment Committee. Please note that while David Hay co-manages the investment program on behalf of Evergreen clients, this publication is not affiliated with Evergreen and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Investment Committee. The information herein reflects the personal views of David Hay as a seasoned investor in the financial markets and any recommendations noted may be materially different than the investment strategies that Evergreen manages on behalf of, or recommends to, its clients.

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this material, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material has been distributed solely for informational and educational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or to participate in any trading strategy. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, adequacy, or completeness cannot be guaranteed, and David Hay makes no representation as to its accuracy, adequacy, or completeness.

The information herein is based on David Hay’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions regarding future events based on information available to David Hay on a formal and informal basis as of the date of this publication. The material may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that any opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary discussed herein will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. Actual experience may not reflect all of these opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary.

David Hay shall have no responsibility for: (i) determining that any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein is suitable for any particular reader; (ii) monitoring whether any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein continues to be suitable for any reader; or (iii) tailoring any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein to any particular reader’s investment objectives, guidelines, or restrictions. Receipt of this material does not, by itself, imply that David Hay has an advisory agreement, oral or otherwise, with any reader.

David Hay serves on the Investment Committee in his capacity as Co-Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal (“Evergreen”), registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The registration of Evergreen in no way implies a certain level of skill or expertise or that the SEC has endorsed the firm or David Hay. Investment decisions for Evergreen clients are made by the Evergreen Investment Committee. Please note that while David Hay co-manages the investment program on behalf of Evergreen clients, this publication is not affiliated with Evergreen and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Investment Committee. The information herein reflects the personal views of David Hay as a seasoned investor in the financial markets and any recommendations noted may be materially different than the investment strategies that Evergreen manages on behalf of, or recommends to, its clients.

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this material, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

Thanks David. Seems to be a different post than you intended but it was still really interesting to see his work.

You posted the weekly article rather than the "average investor" article!