Friday Haymaker

A Humble Nod to Christopher Wood

“Let me give you my vision. A man’s right to work as he will to spend what he earns, to own property, to have the State as servant and not as master; these are the British inheritance. They are the essence of a free economy. And on that freedom all our others depend."

“The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people's money.”

Both passages attributable to the “Iron Lady” herself, Margaret Thatcher

Charts of the Week

The easing of financial conditions since late October has been extraordinary. (In the chart below, higher means easier.) Making this all the more remarkable is that the Fed hasn’t lifted a finger to cut rates. In fact, it is now going out of its way to say it won’t do so anytime soon. The catalysts behind the Big Easing have been a decline in bond market yields and also a further narrowing of credit spreads. The latter represent the yield premium on corporate bonds versus U.S. Treasurys (USTs). When this differential shrinks, it is very bullish for stocks and corporate debt. When it widens, especially significantly, trouble almost always follows close behind. The narrowing of junk bond spreads, for example, from ~6% over in the summer of 2022 to around 3.5% today, has been a critical factor in igniting the rally that has pushed the S&P 500 above 5000 today for the first time. (It is fair to note that 8 of the 11 S&P sectors remain well below their all-time highs set in 2023; note that spreads have decreased approximately 1% — 100 basis points — since late October.) The below, combined with a federal deficit running around $1.6 trillion, or around 6% of GDP, is undoubtedly helping to postpone a recession and a bear market. By the way, deficits in the 6% vicinity usually only happen during wars or severe economic contractions. (Note, the deficit has been downwardly revised for this federal fiscal year, ending 9/30/2024; this strikes me as optimistic considering that the first quarter’s red ink is running well above last year.)

Areas of the economy in which the federal government has been heavily involved have seen much faster price increases than those that have been dominated by the private sector. In certain of the latter sectors, prices have actually fallen. This same phenomenon has been seen in many other countries, particularly those where the government has taken over direct control of the means of production. In some nations, this has led to hyper- not just high inflation.

Will The Wonders of Socialism Never Cease?

While I realize the name Christopher Wood isn’t as well known to Haymaker readers as are many of my other go-to sources, I nonetheless religiously read his weekly GREED & Fear publication. Typically, he focuses on the usual macroeconomic and financial market events I frequently cover, but in a concise and chart-rich format. (You’ll notice King’s English spellings throughout.)

On February 1st, however, Christopher took on one of the most illuminating case studies in the “wonders” of socialism: Argentina’s economy in the post-WWII era. To say it has been an “anti-miracle” is being most charitable. Truthfully, it’s been an economic disaster unparalleled in South America, save for that other glorious bastion of collectivism: Venezuela.

The latter, of course, has managed to destroy its economy and impoverish its citizens in just 25 years. Firebrand socialist Hugo Chavez was elected president in 1999 when Venezuela’s oil output was around 3.5 million barrels/day. This rendered it one of South America’s wealthiest nations. Under his “inspired” leadership, its oil production began to erode despite oil reserves that were, and are, even greater than Saudi Arabia’s.

By the time Mr. Chavez succumbed to cancer in 2013, annual oil production averaged 2.7 million barrels/day. But it was under his handpicked successor that output did a cliff dive. Venezuela now produces fewer than 800,000 barrels/day. This is barely (barrel-y) enough to meet its own consumption. Consequently, its once immense oil export revenue has dwindled to essentially a trickle.

What it has excelled at producing is inflation. While raging consumer prices were a problem before Mr. Chavez took office, and he did bring their rate of change down in the early years of his term, the CPI was increasing at a 40% annual rate by his death. But, as with oil production, it was under Mr. Maduro that the nightmare became Kafkaesque. By 2015, it had nearly sextupled to over 250%. But that would soon seem like the good old days.

Three years later it was running at the Weimar Germany-like rate of 63,000%. Unsurprisingly, the economy was in shambles and Venezuelans were fleeing by the millions. The somewhat good news is that it has now cooled all the way down to 360%. Frankly, how people manage to survive under such horrific conditions is beyond me.

Returning to Argentina and Christopher Wood, the recent election of Javier Milei in that country has attracted international attention. His speech last month to the Davos intelligentsia received widespread attention, both flattering and disparaging. As Christopher wrote in his February 1st note, he is a fan of what Mr. Milei is attempting, writing:

[I] admit to being entirely sympathetic to the view expressed by the self-confessed anarcho-capitalist in terms of his critique of the Western world’s adoption of an increasingly collectivist approach that (quoting Milei) ‘inexorably leads to socialism, and therefore to poverty.’

Mr. Milei went on to drive home his main points which should rivet attention in the U.S. and especially in states like California:

The case of Argentina is an empirical demonstration that no matter how rich you may be…if measures are adopted that hinder the free functioning of markets, competition, price systems, trade and ownership of private property, the only possible fate is poverty.

Part of that empirical demonstration is that, per Christopher, Argentina’s real GDP per capita as a percentage of U.S. real GDP per capita crashed from 40% in 1961 to 21% in 2022. (While he doesn’t cite this statistic, it was 80% of US GDP per capita in 1905, roughly equivalent to England’s ratio vis-à-vis America’s at the dawn of the 20th Century). In contrast to the high-speed collapse by Venezuela’s economy, it took several decades for Argentina’s drain-circling to become an existential crisis.

The process started under Juan Peron and his charismatic wife, Eva, in the 1940s (sadly, Argentina would cry almost endlessly as a result of their policies). However, as noted above, Argentina remained a comparatively wealthy country into the early 1960s. Although there were repeated attempts to reverse Peronism’s downward spiral, these have consistently failed. Many expect the same fate for Mr. Milei’s draconian rescue package but, like Christopher, I’m rooting hard for him.

(By the way, Argentina’s neighbor to the west, Chile, instituted a similar set of reforms in the 1970s under the guidance of a team from the Chicago School of Economics. That was, of course, where Milton Friedman hung his shingle in those days. After some very difficult early years, which included inexcusable political atrocities, mostly by the right-wing military, a true economic miracle did unfold, as evidenced by the beauty of that country’s capital city. Moreover, inflation has largely oscillated around 5%, or even less, over the last 30 years.)

Here are some more particularly salient excerpts from his missive:

This macroeconomic debacle is the consequence of years of Peronist rule, a political party which has a total contempt for the market-driven price signals beloved by devotees of Austrian economics, including GREED & fear. So disastrous have been their policies that the Merval Index fell 48% in US dollar terms the day after the Peronists won, surprisingly, the presidential primary election in August 2019 bringing an end to the reformist government of former President Mauricio Macri.

* * * * * * *

If Macri’s approach was gradualist, Milei aims at shock therapy. In this respect, his best hope of success, in terms of keeping the population with him, is that he campaigned on the need to suffer if Argentina is to have any hope of solving its chronic economic problems. Inflation reached 211.4% YoY in December.

* * * * * * *

If the action in the Lower House of the legislature is dominating headlines at present, the core of Milei’s shock approach is a proposed five percentage point cut in the fiscal deficit this year from 5% of GDP to zero, following a 54% devaluation announced in mid-December when he took power. Meanwhile, a 17.5% tax levy on dollar purchases for imports of goods and services, up from the previous 7.5%, means the government is focused on accumulating dollars.

* * * * * * *

The “good” news is that the shock measures are already triggering a sharp slowdown in the economy. GREED & fear heard that sales in a large supermarket chain were down 30% in the month of January. For the sharper the slowdown the quicker inflation, currently running at 25% a month, should fall after the initial devaluation triggered spike. The view in the Argentine capital is that the next three to four months will be critical. If there is no sign of inflation declining by the middle of the year, then it is anticipated that there will be a widespread questioning of the reform programme.

* * * * * * *

The era of “convertibility” between 1991 and 2001 was the last time Argentina enjoyed extended economic stability. The peso was pegged to the dollar during this period. GREED & fear was last in Argentina a year or so before convertibility blew up when fiscal deterioration triggered an initial 29% devaluation to 1.4 in early January 2002 and a 74% devaluation to 3.86 in 1H02.

* * * * * * *

* * * * * * *

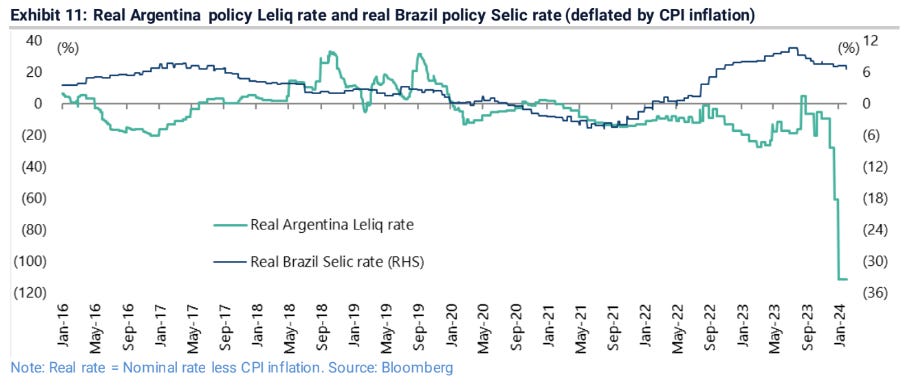

Meanwhile, from a longer-term perspective, it is interesting to note the contrasting experience of Argentina and Brazil in recent decades in terms of the economic history. As discussed here last week (see GREED & fear – Risk and parity, 25 January 2024), Brazil has stood out in the quanto easing (Haymaker note: the Fed’s former QE policy) era by maintaining high real interest rates. But this has been a feature of the country for decades. The result has been a system where Brazilians were prepared to keep their money at home since they were paid a decent return on their capital though, admittedly, the availability of high real rates meant that bonds have usually been favoured over stocks as continues to be the case today.

If creditors have been favoured over debtors in Brazil, the exact opposite has been the case in Argentina whose historical experience has been the precise opposite; namely the absence of real interest rates (see Exhibit 11). The result has been wealthy Argentinians keeping as little of their funds in the country as possible save what they need to conduct business.

With Milei now determined to stop the central bank financing the government (i.e. to do the exact opposite of what happens in quanto easing), it is worth noting again the remarkable complacency surrounding the continuing conduct of unorthodox monetary policy in the G7 world in the post-2008 era. This can persist so long as G7 (Haymaker note: rich country) government bonds are considered “risk free” whereas emerging market bonds are not, most particularly G7 government bond markets dependent on foreign inflows. But such conventions are based more on custom rather than logic and can certainly be challenged at same point in the event of continued fiscal deterioration and renewed central bank financing of government, which is what would happen in the case of renewed G7 central bank balance sheet expansion.

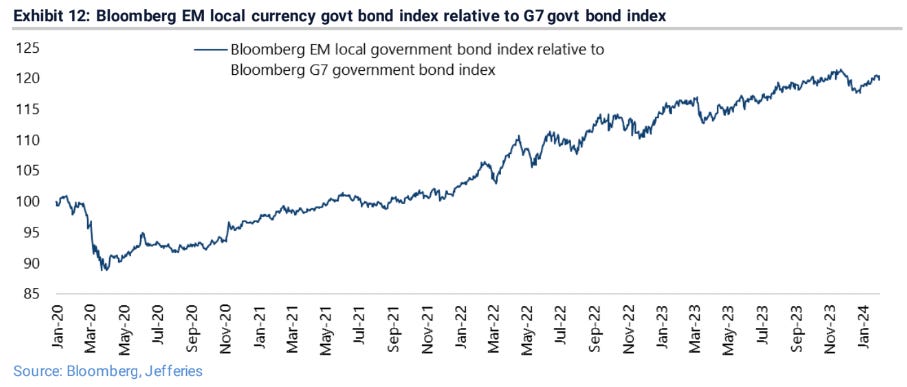

In this respect, GREED & fear makes the point again that the massive outperformance of local currency emerging market government bonds in US dollar terms in the past four years shows that investors are beginning to reward good behaviour in terms of the valuation of bonds issued by emerging market governments relative to their entitled G7 counterparts (see Exhibit 12). Clearly, Argentina has not been a part of this trade. But its new president wants to go in the precise opposite direction from that in which the Western world is heading, with its increasingly socialised credit system, as he made abundantly clear in his comments to the Davos mob. That, aside from the money that can be made or lost, is why the Argentine experiment is worth monitoring.

For those who prefer the quick upload as to the sort of leadership Milei is promising to embody, we’ve provided a link to this highly publicized and controversial speech at the end of this piece.

Among the reasons I believe this is so essential is because of the global trend toward autocratic and collectivist economic policies, including in America. Younger generations are particularly open to both of these toxic political and economic models. They are often hidden under the guise of populism with its inevitable cult-like following for the charismatic “agent of change”.

This alarming pattern was reinforced to me by a recent podcast I listened to this week between my friend David Lin and demographer/historian par excellence, Neil Howe. As many of you are aware, I feel Neil’s latest book, The Fourth Turning is Here, is must-reading for all investors. One of his main points is that we are in the midst of the fourth mega-crisis since our nation’s founding. Such severe dislocations pose the risk of a demagogue coming on the scene promising stability and prosperity. Frequently, democratic processes and institutions are lost in the paradigm shift. (We’ve also included a link to this discussion.)

Link: Reuters

Video: The David Lin Report

There’s still time to correct the dangerous course we are on in the West right now, and we can start by taking a page from Milei’s playbook, as he’s personally experienced socialism in all its inevitable misery. In my view, which I believe history absolutely confirms, collectivism is the classic case of an economic theory that works well until it’s forced into an uncomfortable embrace with reality. The great irony of these experiences is that they impoverish the very citizens they were meant to benefit, the ultimate law of unintended consequences.

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material has been distributed solely for informational and educational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or to participate in any trading strategy. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, adequacy, or completeness cannot be guaranteed, and David Hay makes no representation as to its accuracy, adequacy, or completeness.

The information herein is based on David Hay’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions regarding future events based on information available to David Hay on a formal and informal basis as of the date of this publication. The material may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that any opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary discussed herein will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. Actual experience may not reflect all of these opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary.

David Hay shall have no responsibility for: (i) determining that any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein is suitable for any particular reader; (ii) monitoring whether any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein continues to be suitable for any reader; or (iii) tailoring any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein to any particular reader’s investment objectives, guidelines, or restrictions. Receipt of this material does not, by itself, imply that David Hay has an advisory agreement, oral or otherwise, with any reader.

David Hay serves on the Investment Committee in his capacity as Co-Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal (“Evergreen”), registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The registration of Evergreen in no way implies a certain level of skill or expertise or that the SEC has endorsed the firm or David Hay. Investment decisions for Evergreen clients are made by the Evergreen Investment Committee. Please note that while David Hay co-manages the investment program on behalf of Evergreen clients, this publication is not affiliated with Evergreen and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Investment Committee. The information herein reflects the personal views of David Hay as a seasoned investor in the financial markets and any recommendations noted may be materially different than the investment strategies that Evergreen manages on behalf of, or recommends to, its clients.

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this material, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.

I picked up a very small amount of 2029 Argentina bonds in August 2022. They are up 71%!

Did you write this article, David? Not particularly enlightening this week...