Making Hay Monday - September 18th, 2023

High-level macro-market insights, actionable economic forecasts, and plenty of friendly candor to give you a fighting chance in the day's financial fray.

Charts of the Week

Goldman Sachs recently lowered its recession odds to just 15%. This attracted considerable attention in the financial media, despite that its former chief strategist did not see the Great Recession looming even in late 2007. In fact, in December 2007 she opined that by mid-year 2008, the U.S. economy would be picking up steam: “At that point, recessionary fears will fade away and the market can do much better.” Oops! However, it’s fair to note Goldman is not alone and that most of Wall Street agrees with its call that a recession is unlikely. The Fed’s Beige Book, which contains its Summary of Commentary on Current Economic Conditions, published eight times a year, is painting a far darker picture. Yet, despite the visual shown below, the Fed itself is also in the soft-/no-landing camp.

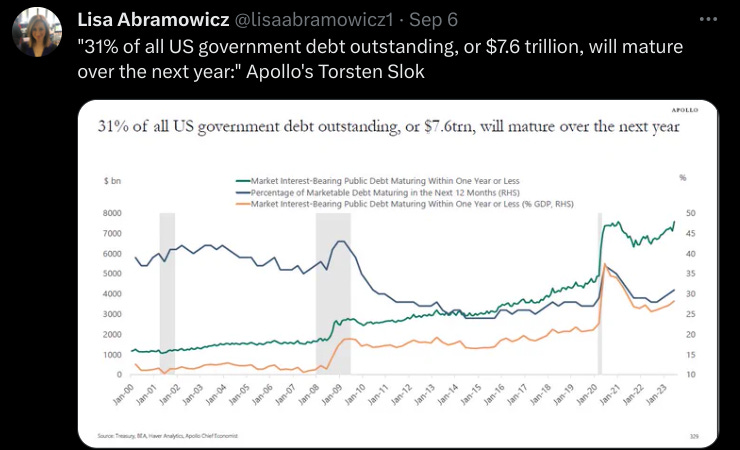

There is little doubt the interest rate downtrend from December 31st, 1999, until August of 2020 was a persistent catalyst for both higher stock prices and corporate earnings. Since the yield trough over three years ago, this effect has been fading. During 2022’s twin bear markets in stock and bonds, the rate reversal caused major market dislocations. This year, that has flipped for stocks but not Treasury bonds, which are on track for another negative return. This would make three down years in a row, an unprecedented event since at least 1928. With nearly $8 trillion of U.S. government debt maturing over the next year, almost one-third of total Treasury bonds outstanding, the potential for even higher rates is far from trivial. In fact, I would argue it’s highly probable.

The Trends Are No Longer Our Friends

“It’s time for markets to fully digest how constrained central banks are going to be relative to the last 30, 40,years, when every time there was a tiny murmur of a problem, you could just lower rates and print money.” -Karen Karniol-Tambour, Bridgewater Associate’s co-CIO. (Her firm manages over $150 billion of client assets; it is the world’s largest hedge fund, with one of the industry’s best risk-adjusted performance numbers.)

“The bamboo that bends is stronger than the oak that resists.” -Japanese proverb

First off, partially because I know many readers like to be exposed to positive commentary, as well as the more realistic type, I plan to do exactly that in my upcoming webinar. Specifically, I plan to focus on the many ways I could be wrong about stocks, bonds, recession, inflation, and our general societal malaise.

As usual, this will be for select clients and our Founding Members. If you’re not either one, we fervently hope that will change soon. However, we do plan to offer a sneak preview of what you’re missing to all Haymaker subscribers, paid and the other kind.

In the meantime, though, there are a few topics of the less ebullient nature I’d like to get off my chest. The first pertains to the improbability of another run of favorable financial fortune, such as we had since the start of this century/millennium.

For starters, how likely is it that interest rates will decline like they did from 2000 to 2020? The 10-year T-note kicked off the 21st century sporting a yield of around 6½%. By the summer of 2020, it nearly touched ½%. (Yes, as in, 0.5%.)

Chart of the Yield on the 10-Year T-Note From 12/31/99 Through August 2020

Of course, since then it’s been a much different story with yields on the 10-year now at 4.3% and threatening to head higher. Remarkably, as least for now, that yield spike has done little to impair the stock market, save for last year, which was pretty much a disaster for both stocks and bonds.

However, even though stocks have been surprisingly resilient in the face of much higher interest rates, that’s not likely to be the case with corporate earnings. As you likely know, those are already declining. This is despite that the U.S. economy is not (yet) in recession. There is little question that the collapse by interest rates since the end of the 1990s was a powerful tailwind for profits. It also turbocharged Corporate America’s favorite insider wealth creation machine: share buybacks.

Lower borrowing costs made these even more beneficial to earnings per share, though, often, repurchases actually reduced profits in dollar terms. After all, even low interest rates are an incremental cost when large amounts of debt are incurred to finance buybacks. Even once-debt-free cash cows like Microsoft and Apple borrowed vast sums in order to acquire their own shares. In fairness, those turned out to be an extremely productive use of capital.

Yet, with rates up as much as they are now, it’s nearly a given that buybacks will be much less prevalent. Thus, there is a double whammy to earnings per share: higher interest costs and reduced shrinkage of the share count. (The latter juices earnings on a per-share basis.)

Then there is the matter of taxes. Corporate America’s remittances to the federal government have been receding this century at a rate similar to interest costs. That is extremely unlikely to continue. In fact, with the increasingly perilous financial condition of the federal government becoming obvious to any sentient human being (i.e., exclusive of members of the administration and Congress), higher taxes on corporate profits are almost a given.

Not yet a paid Haymaker subscriber? Complete the brief survey linked below and we’ll set you up with a 90-day trial at no cost.

My Aussie mate Gerard Minack ran the following chart last May. It drives home the above far more effectively than I can with mere words.