Making Hay Monday - September 11th, 2023

High-level macro-market insights, actionable economic forecasts, and plenty of friendly candor to give you a fighting chance in the day's financial fray.

Charts of the Week

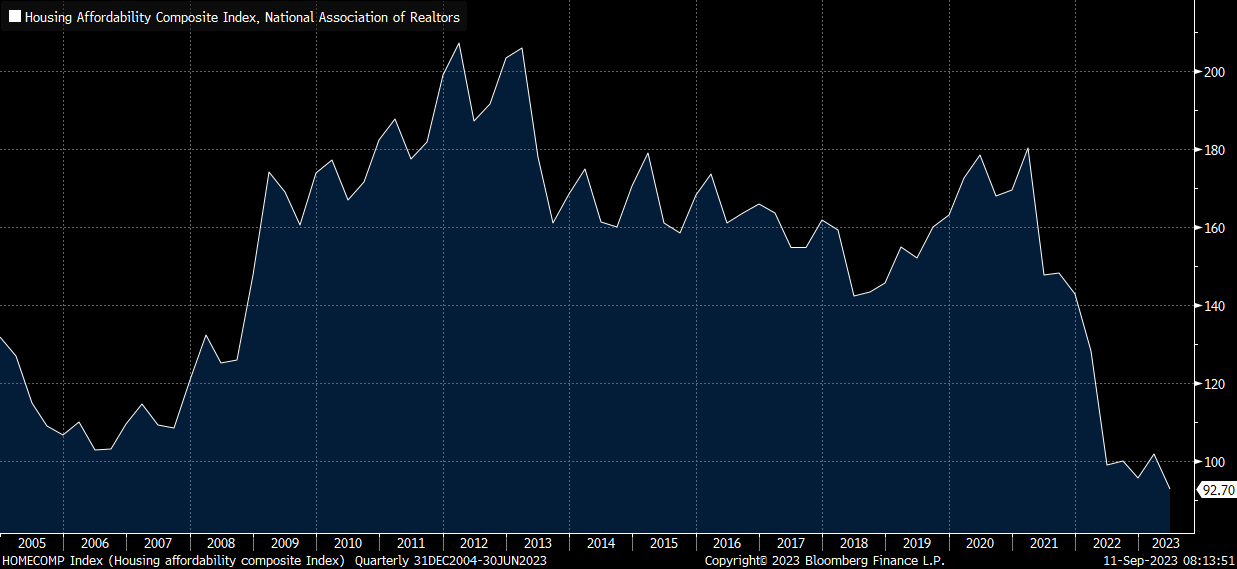

The striking divergence between the Homebuilder ETF (XHB) recently trading near its all-time high and the severe challenges facing this industry has been an intermittent focus of this newsletter. It’s also why that ETF, which may have made a double-top when it hit 85 this summer, has been on our Down For The Count List since May 15th (prematurely, I might add.) Lately, it has been weakening, perhaps feeling the gravitational pull of flaccid homebuyer traffic and the worst affordability in decades. Frankly, it’s shocking that affordability is at now at a lower level than it was in 2006, at the height of the biggest housing bubble in U.S. history. A limited supply of existing homes for sale, with most potential sellers understandably reluctant to give up their current low-rate mortgages, has been a major supporting factor for housing prices. Could a looming “Airbnbust” scenario create a supply tsunami, altering these dynamics? At the end of the paid section, we’ve included a link to an illuminating podcast on this topic by the person who coined that term.

Housing Affordability - NAR Data (Click chart to expand)

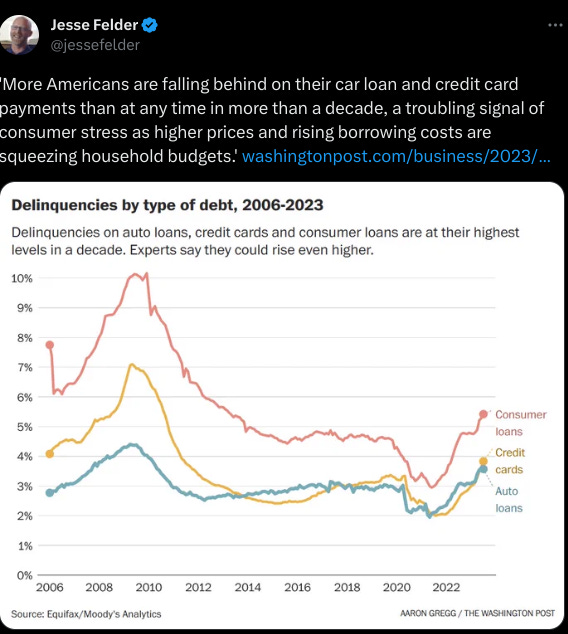

The Energizer Bunny also known as the U.S. consumer? Maybe, not so much. The charts below indicate two disturbing realities. The first is the left-behind nature for most Americans since 1980, near the time when the great bull markets in stocks, bonds, and real estate were set to begin roaring. This period also coincided with a decided shift of the fruits of economic growth toward corporate profits and away from labor. Since 1980, per capita GDP has more than tripled while wages have increased far less, 114%. The second shows the surge in revolving consumer loan balances, mostly credit cards. As noted in prior Haymaker editions, it’s extraordinary that interest rates on the latter are now over 20%. That’s higher than they were in 1981 when former Fed chairman Paul Volcker was crushing inflation (and the economy) with a prime rate of 21%. For sure, wealthier Americans are in excellent shape with stocks back near their highs, at the same time that they are earning 5% plus on their cash.

FT Employed vs Real GDI (Click chart to expand)

Bond Obsession Syndrome

“Every recession starts out looking like a soft landing.” The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip (September 9th)

“Gentlemen prefer bonds.” -Andrew Mellon

“If the Fed was getting things right over the past two decades, it would not have an $8 Trillion balance sheet.” -JonesTrading’s Chief Markets Strategist, Mike O’Rourke

As I’ve admitted in the past, I am wrestling with — if not agonizing over — the question of whether long Treasury bonds are now a buy. Because I have repeatedly made the case for an impending recession, the answer should logically be yes. That’s certainly what I have done over the last 40 years whenever I’ve come to believe an economic faceplant was close at hand.

However, on Friday I came across a highly relevant snippet from The Flow Show by BofA Merrill’s Michael Hartnett. If you’ve never seen it (and I plan to run one in the near future), these are made up of a series of factoids and charts in a terse, matter-of-fact style that would make Hemingway envious. To wit:

Tales of the Unexpected: the big risk recession and higher unemployment cause higher not lower long-term government bond yields as markets discount fiscal policy panic, politicians spending to avert social & political unrest; yields then rise to punishing levels causing long and hard landing; we use any rallies in risk assets in coming months to get defensive and position for hard landing.

The reason I added italics to this excerpt is because that section gets to the heart of one of my biggest worry points: rising rates in a recession due to the Federal Fiscal Funding Fiasco. Essentially, there is the very real possibility — maybe probability — that the U.S. government is unable to fund itself without the Fed resuming its familiar role of debt monetizer. In direct terms, this means using the Fed’s ability to create money out of nothing and use it to buy U.S. Treasurys (USTs) at rates no willing buyer would commit their capital. This distinct threat is totally contrary to what the consensus of bond investors believe (though there are increasing signs that’s changing).

On the other hand, there appears to be tremendous negativity toward USTs in the futures market, as I’ve noted previously. This is usually a most bullish situation, per earlier Haymaker editions. However, in our August 28th edition, I relayed a short excerpt from Kevin Muir, author of The MacroTourist. At that point, I committed to running a more detailed version. That time is now.

Not yet a paid Haymaker subscriber? Complete the brief survey linked below and we’ll set you up with a 90-day trial at no cost.

Some readers may think I have an unhealthy obsession with the 10-year T-note market. That may be a valid criticism. However, in my defense, I’d cite the reality that interest rates on this government obligation are vital to a multitude of important segments of the economy. Home lending is one prime example, but auto loans are another.

But the direction of yields on the 10-year UST is also profoundly impacting the financial markets. Obviously, bond prices are directly affected by rate changes on it, with higher rates being a negative. But that also tends to be the case with stock prices and real estate values, as well. Essentially, it’s tough to find another security which has such powerful and pervasive impacts on so many economically and financially critical areas.

There is a distinct tendency for dramatically higher interest rates, such as what we’ve seen over the last year, to make the rich richer and the poor poorer, at least on a cash flow basis. (As far as asset prices go, that’s a different story, per the above.) This is clearly the opposite effect we’d like to see in a society in which the asset-ownership scales tip heavily in favor of the well-to-do. The two images below, courtesy of my good friend Jesse Felder, get to the heart of that matter.

The foregoing are further reasons to expect interest rates to reverse direction soon. However, as Kevin Muir will persuasively argue in the behind-the-paywall section of this Making Hay Monday edition, there may be far too many bond bulls right now who are already way out over their skis on longer-duration USTs.