LVG Haymaker

A Piece From Haymaker Co-Star, Louis-Vincent Gave!

“Pandemics fast forward history.” -Yuval Noah Harari, Israeli author and historian

“The greatest credit event of all would be a recession in which U.S. yields went up, not down.” -BofA Merrill’s Michael Hartnett

Greetings, Haymaker Readers and Subscribers!

Well, we promised you all regular content from my friend and partner, Gavekal’s Louis-Vincent Gave, and delivering early on that promise is in order. And how better to initiate this new publishing cross-pollination project than with LVG’s musings on the topic of just what cyclical economic/marketplace changes we should all be looking out for in 2024? And there are some big ones.

I won’t steal any of the article’s thunder in my introduction, but I should note that the piece below has been slightly modified in a few places and has been trimmed back somewhat to make room for several blocks of detailed Haymaker commentary which you’ll see throughout. These are relatively brief passages meant to add supporting context to the many points Louis is articulating in this expansive piece. We hope you enjoy the experimental format.

Let us know in the comments section how you like the material and what other topics you’d like us to cover in the months ahead.

Thank you!

David “The Haymaker” Hay

But first, your Charts of the Week!

Yield on the Two-year Japanese Government Bond (JGB) Since 2014

(Upper-line corresponds to a 0% yield… or non-yield) - (Click chart to expand)

Yield on the 10-Year JGB Since 2014 (breakout points correspond to 0.17% and 0.52%, respectively) - (Click chart to expand)

Since the start of 2022, the yield on the two-year Japanese government bond (JGB) has clearly shattered upside resistance. The first penetration of this was when yields rose to minus 0.1%. (Japan was an early adopter of negative interest rates, one of the most bizarre and questionably effective “remedies” ever concocted by policymakers.) This was another example of the follow-through that happens when a well-established range is broken, in this case to the upside. In mid-2023, two-year yields began to consistently trade in positive territory, albeit still at microscopic levels. 10-year resistance has also been decisively taken out as well. This suggests JGB yields are headed higher yet despite the Bank of Japan’s halting attempt to allow rates to catch up with inflation. Because the yen has been so heavily used as a funding currency to invest in other markets, should JGB yields continue running up it could have profound implications for global asset prices.

The ill-advised shutdown of the global economy during Covid was unquestionably the main reason federal deficits exploded in 2020 and 2021. However, even prior to that they were running at excessive levels due to the Trump administration’s massive 2017 indefensible gift tax cut to Corporate America. (As realists predicted at the time, it did not result in an offsetting revenue windfall to the U.S. Treasury.) More disturbingly, deficits have remained at crisis-type levels even after the ravages of the pandemic have faded away and the economy has been growing at respectable clip. The reality is that never before have deficits been this large outside of the total economic collapse of the Great Depression when unemployment in the USA rose to nearly 20%. By contrast, today it is sub-4%. With the 2024 presidential election looking like a rematch of 2020, the prospects for meaningful budget deficit reduction under either a second Biden or Trump administration look bleak.

It’s Different This Time: Cyclical Changes For 2024

Louis-Vincent Gave

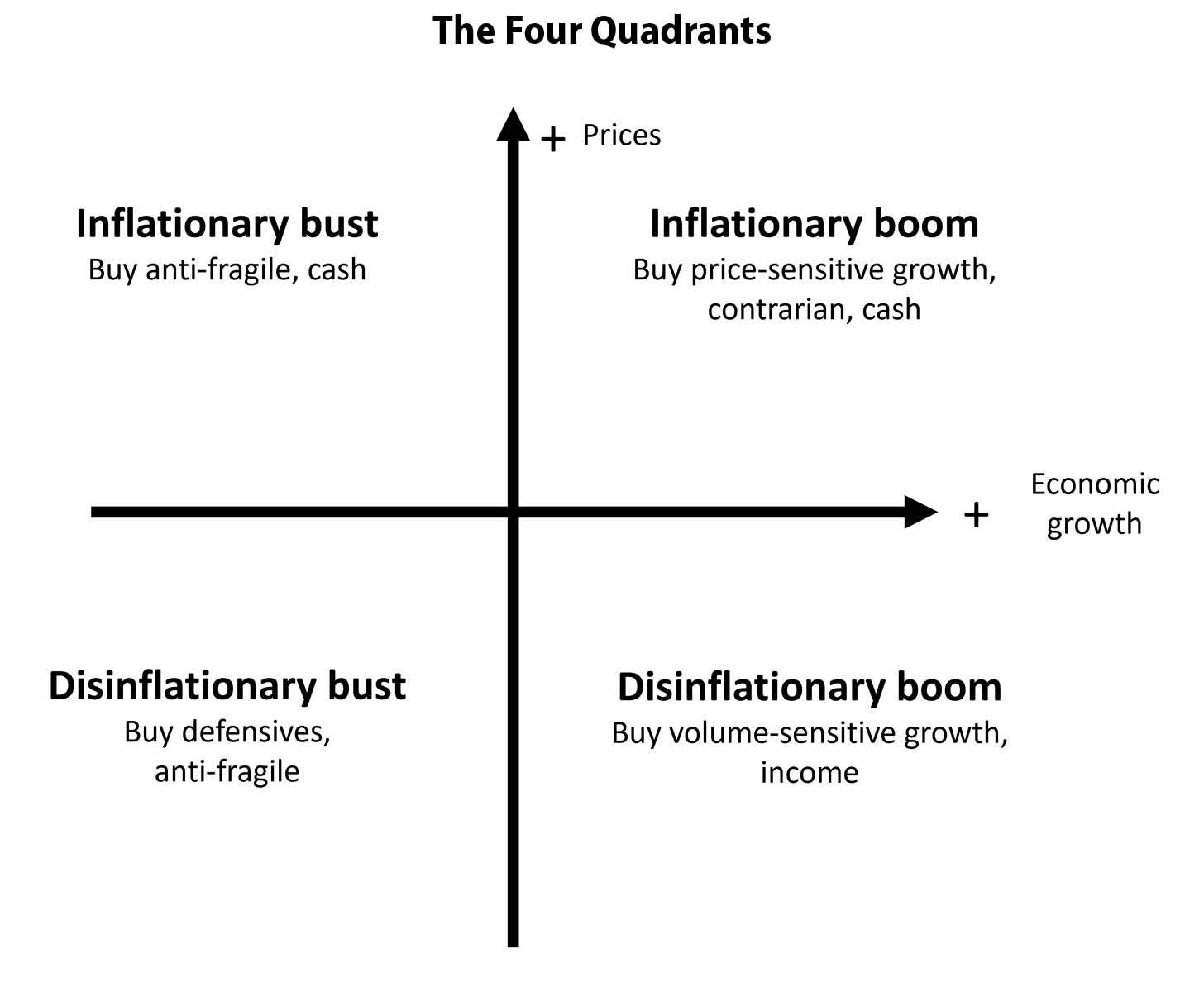

As investors put a bow on 2023, the general consensus was that growth both in the US and globally would slow. But not slow all the way into a recession, in part thanks to falling energy prices (an effective tax cut for most consumers) and a roll-over in inflation (boosting consumers’ disposable income). In turn, milder growth and lower inflation would push the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates. The happy days of the disinflationary boom (bottom right on the diagrams below) were hence around the corner. Such an investment environment was positive for bonds (cue a massive rally in November and December) and growth stocks everywhere.

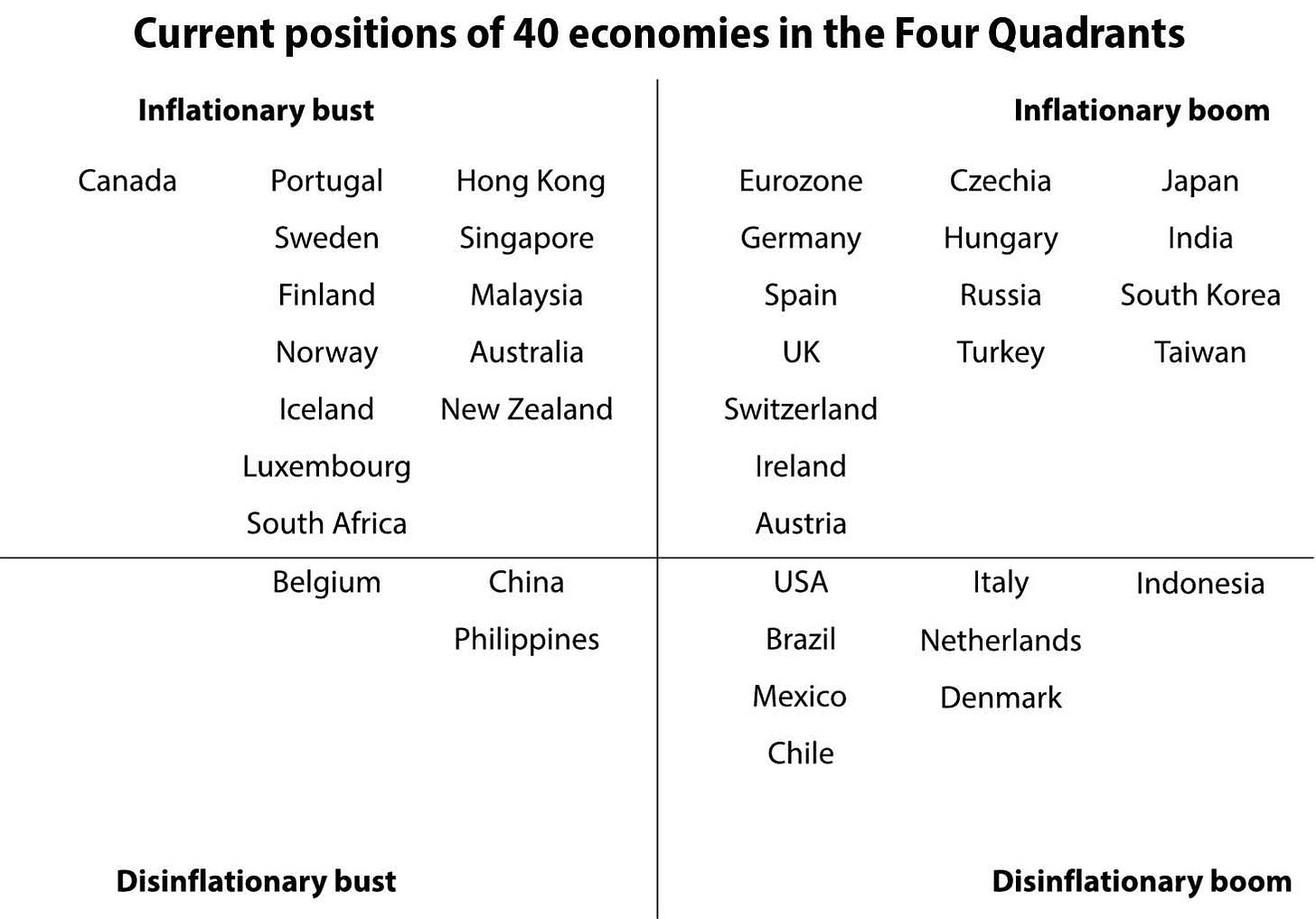

Yet, never have the world’s major economies sent out such conflicting signals. Sure, the US is back to signaling a disinflationary boom, but China is indicating a disinflationary bust, commodity producers like Canada, Australia, South Africa and Norway are telling us the world is set to face an inflationary bust, while most of Europe, Japan and the rest of Asia are pointing the way to an inflationary boom!

One can cogently make a case for any of these four scenarios today, which means things are a mess. Having said that, I will argue for growth (and to a lesser extent inflation), for the following reasons.

Haymaker Comments: Louis’s observation that things are a mess, or at least extremely muddled right now, is consistent with my Edward R. Murrow quote from last week that anyone who isn’t confused really doesn’t understand the situation.

The Four Quadrant matrix shown above is a Gavekal staple from the earliest days of the firm’s formation. It’s a helpful way to look at the world, especially when it is fairly clear in which quadrant global financial and economic conditions currently reside. That’s definitely not the case at this time when there are such strong countervailing forces. As we get deeper into his note, we’ll seem some reasons why it’s so difficult to have a high degree of conviction as to where the global economy is right now… much less, where it will be as the year unfolds.