“The industrial recession is a global phenomenon.” -Danielle DiMartino Booth, 7/27/22

“I think we now understand better how little we understand about inflation.” -Jay Powell

“Through our wholesale channel, there’s really no indication of any demand destruction…in June we actually set sales records.” -Gasoline-refining, and market giant Valero Energy’s executive VP, Gary Simmons

Source: Shutterstock

As many Haymaker readers know, I’ve been active on the podcast circuit lately with appearances on Adam Taggart’s Wealthion, Tom Bodrovics’ Palisades Gold Radio, and Erik Townsend’s MacroVoices. These experiences are always exhilarating but, inevitably, I mentally kick myself afterwards for not having brought up some critical material or for having failed to fully develop a few important ideas.

As a result, I felt a Haymaker edition devoted to summarizing, clarifying and expanding on what I recently said might be helpful to our subscribers. In fact, there’s so much to cover that this is the first of a two-part Haymaker.

For your sake and mine, I thought it would be best to break the topics down into broad categories. Based on the surprisingly hefty jobs number released last week, it seems appropriate to start with the overarching Recession/No Recession debate.

The Economy: On June 20th, I grudgingly joined ranks with those who believe a recession is imminent. Readers who’ve been with us for a while realize this is not what I expected to be saying and writing this summer. Prior to the invasion of Ukraine, I felt 2022 would bring plenty of economic growth along with a healthy dose of inflation. Once V. Putin was putting on the blitz, my faith in that call diminished materially. Ironically, the shortage of many key commodities that his attack caused, especially energy, worsened the growth part of my forecast while intensifying its high inflation element.

To learn more about Evergreen Gavekal, where the Haymaker himself serves as Co-CIO, click below.

This is where the situation gets complicated. As you may know, there are two components to overall GDP increases: the first is real growth; the second is inflation. This leads to the twin calculations of real and nominal GDP, with the latter incorporating both increased activity and inflation. You’re probably also aware that for the first half of 2022, real growth appears to have been negative; however, that could flip back to positive based on future revisions. The aforementioned blowout jobs number, double initial expectations, makes that more likely.

Putting this aside, even if the economy shrank in real terms in the first two quarters, nominal GDP was extremely strong, driven, of course, by inflation. Consequently, those who were predicting healthy growth could say “I told you so” while those who were anticipating a recession could also argue they were right.

Yet, the official arbiter of when a recession begins is the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER). Their four main criteria are real sales, real income, production and employment. Note the “real” connected to the first two, meaning after inflation. On this basis, the first two have gone negative, as has production or output. The one that remains positive is, of course, employment, which just became even more so.

The problem is that jobs data are one of the most lagging of indicators, as all economists concede. This is why the NBER’s recession declarations often happen late into a downturn. There is another complicating factor, not that one is needed or welcome. It relates to an esoteric adjustment calculation known as the birth/death model.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) tries to estimate how many new businesses are formed (births) or existing ones shut down (deaths). Usually, they are fairly accurate. However, at economic inflections points, like at the start of an expansion or contraction, these generate false signals. In the former case, they are too negative and, in the latter, too positive.

Accordingly, if we are presently in the early stages of a downturn, the official jobs data, which includes the birth/death adjustment, are most likely generating excessive estimates of job creation. This is because, assuming the economy is downshifting significantly, there are a lot more businesses dying right now than the BLS is assuming.

On that assumption, one point I’ve made in two of my recent podcasts is the speed with which this economic deceleration is occurring. The extremely rapid rise by initial claims for unemployment is one example of that. These are now up by roughly 82,000 from the trough on a four-week moving average basis. Typically, a 65,000 jump is the demarcation line that denotes a recession is nigh. Admittedly, initial jobless claims started at a very low level, reflective of how muscular the labor market was earlier in the year. But rock star economists like David Rosenberg — who is very much in the recession camp, by the way — believe it’s the rate of change that matters the most. What is for sure is that initial jobless claims are a leading indicator for what is otherwise a lagging indicator (as noted above).

There is another advance reading on the jobs market: the Household Survey. As its name suggests, it is based on contacting consumers to find out what their employment status is at a given point in time. It does a far better job of picking up trend changes, but it does have the drawback of being quite volatile. Currently, it, too, is emitting warning signals that the employment picture is in the process of darkening.

Beyond that aspect, I think the economy has another big problem: The stronger the labor market appears to be, even if it’s based on lagging data, the more the Fed feels compelled to tighten. Because of the blockbuster employment report, the odds it will hike by 75 basis points next month have risen considerably, perhaps offset somewhat by Wednesday’s milder inflation reading.

However, as I did mention in at least one of my podcasts, the many crosscurrents out there right now are more intense than I’ve seen in my career. There is a multitude of data now coming out that only occurs prior to or during recessions. These include:

Ø collapsing money supply growth,

Ø falling Leading Economic Indicators in four of the last five months,

Ø the S&P declining 20% or more over a five-month period (notwithstanding the recent rally)

Ø the jump by initial unemployment claims discussed above

Ø the Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) of new orders-inventories going negative

Ø the housing market in free fall

Ø 60% of CEOs expecting a recession

Ø an increasingly inverted yield curve (short rates above longer rates)

Ø a massive hit to consumer balance sheets due to the biggest wealth decline in this year’s first half since the 1930s.

On the other hand, there are numerous other conditions that would seem to make a recession almost inconceivable. To wit, there are still 10.7 million job openings (though they are coming down fast); the fact that after inflation, the fed funds rate is deeply negative (and, therefore, highly stimulative); and Gross Domestic Income (GDI) that is running far stronger than GDP.

Consequently, the Recession/No Recession debate is an intense one with plenty of factoids to back up either contention. However, because there is a preponderance of recession warning signs emerging on a regular basis, and these tend to be more of the leading variety, I’m sticking with my call that a recession is probable. In fact, I believe the NBER will declare one started before year-end, after the usual lengthy delay.

That the Fed is clearly willing – even anxious – to trigger a downturn in order to cut inflation down to size might be the most impactful. And that’s a good segue into the next section…

The Fed. One amazing factoid about the Fed under Jay Powell is that its benchmark real fed funds rate has averaged roughly negative 2% during his four-and-a-half-year reign tenure. There’s that word “real” again. You may have read or heard that Mr. Powell is telling his colleagues inside the Fed’s HQ that he wants to do an imitation of Paul Volcker’s inflation-crushing act. He’s also made it clear he doesn’t want to go down in history as the second coming of Arthur Burns, who gets most of the blame for the inflationary 1970s, at least from a central banker standpoint.

However, as I told Erik Townsend, before Mr. Powell can channel Paul Volcker, he’d better at least try to emulate Arthur Burns first. The reality is that Mr. Burns was NEVER, not even remotely, as far behind the inflation curve as Jay Powell is right now. When inflation shot up to 9% in 1974, Mr. Burns jacked the fed funds rate to 10%, even if he was a few months tardy in doing so. We’ve got the CPI at 9% again but imagine the fed funds rate at 10% today! The resulting financial market chaos and economic devastation would likely exceed even that of the Great Recession.

While a 10% fed funds rate isn’t in the realm of the possible, mostly due to how debt-heavy the U.S. government and the financial system are these days, higher direct and indirect interest costs are almost a lock. As noted earlier, due to the husky official July jobs report, the likelihood of another 0.75% (75 basis points) rate spike next month has to be considered high. That’s the direct rise in rates and, if it happens, it will push the Fed’s benchmark rate to nearly 3%. Several influential Fed officials are advocating ratcheting it up to roughly 4% before year-end.

The indirect part comes from what is known as Quantitative Tightening, the inverse of the Fed’s notorious Quantitative Easing; these are often abbreviated as QT and QE. QE is how the Fed’s balance sheet increased from $700 billion prior to the Global Financial Crisis/Great Recession of 2008 to almost $9 trillion today.

That over $8 trillion expansion of its portfolio was enabled by what I call its Magical Money Machine. It used this digitally fabricated money — reserves it simply created from its computers — to purchase treasury bills, notes and bonds, as well as government-guaranteed mortgages. The Fed buys these from banks like JP Morgan, which are authorized dealers in newly issued U.S. debt instruments. In other words, this is debt monetization whereby the Fed indirectly (and not very indirectly, at that) finances the government’s deficit spending.

That process went into hyperdrive once the pandemic struck. It became the de facto implementation of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which some had proposed as an economic wonder drug even pre-Covid.

To many disinterested observers, including this author, MMT seemed to almost guarantee an inflationary eruption. However, the Fed disagreed, as did many prominent — and, often, highly partisan — economists like Paul Krugman, he of Nobel Prize-winning fame. Mr. Krugman had ranted against MMT when it was first activated under Donald Trump, before becoming a vocal cheerleader as the Biden administration, and the Fed, raised the ante by additional trillions of combined fiscal and monetary stimulus. Naturally, it was funded by QE and the Fed’s Magical Money Machine, fueling what I, and others, have called the Bubble In Everything.

Now, though, that sequence is poised to run in reverse. Most attention is focused on the Fed’s rate-raising campaign. Little thought is given to the implications of QT. The one-two punch of rate hikes and balance sheet shrinkage is the second version of double tightening. The first ended in a market panic in 2018. It’s sobering to consider what a repeat of that will do with financial markets already in a fragile state, irrespective of the recent rally.

It's more art than science to surmise what QT equates to in terms of equivalent rate increases. A credible guesstimate is that each $100 billion is about one-tenth of a percent. That’s roughly what the Fed plans to allow its balance sheet to shrink by each month. Thus, between now and year-end that will be another ½% of effective rate increases. Adding that to the assumed 1.5% (150 basis points) of rate bumps means over 2% of de facto tightening over the next four to five months. That’s a lot when added to what the Fed has already done, elevating the chances of a recession.

The Fed’s goal is to shrink its balance sheet by $2.7 trillion over a multi-year period, amounting to around 2.7% of rate increases if the ratio $100 billion/0.10% is in the ballpark. Personally, I believe it will launch QE 5 way before it ever gets there. (The unofficial fourth iteration of QE began in September of 2019, about six months before Covid hit.)

Several super-astute individuals such as Bridgewater’s Greg Jensen believe we have entered a world with much shorter economic cycles. This view rings true to me and it’s my expectation that the Fed will get caught up in that paradigm. If a recession does arrive later this year and job losses become politically unacceptable, there will need to be another Powell Pause, similar to early 2019. Rate cuts and a cessation of QT will probably not be that far behind.

The problem is that inflation is nearly certain to still be running at 6% or 7% on a year-over-year basis by then, even though the annualized rate of the last few months of 2022 might be a fair bit lower, perhaps around 4%. As a result, the Fed would be in the no-win position of having to choose between letting the economy continue to nosedive or easing into a still-elevated inflation environment.

My bet is that it will choose the second option, especially because a recession will cause an explosion of federal spending and, of course, trillions of new bond issuance. Consequently, the Fed will need to be the bond buyer of first resort once again. If you think our dear central bank is in a wicked dilemma, you are right. Somehow, that thought is lost on the stock market presently, a topic to be discussed next week.

Energy. The most lively discussion I had on this topic, unsurprisingly one of my favorites, was with Erik Townsend. This is likely because he’s extremely knowledgeable about the oil markets.

As most Haymaker readers are no doubt aware, I’m strongly in disagreement with those who believe a recession will crash the demand for oil. Erik, however, is much more concerned about that risk. This gave me a chance to make my case for fuel-switching.

The idea with this, as many of you have previously read in these pages, is that European utilities, and a long list of the largest companies over there, will switch from using fantastically expensive natural gas and coal to oil. To put a number on this point, natural gas on the Continent is equivalent to over $300/barrel, up 28-fold over the last two years. This has driven Europe’s electricity costs to stunning heights. In one of the most shocking aspects of this, baseload electricity prices in Germany and France are equivalent to approximately $700/barrel oil. The “stunning” and “shocking” descriptors are definitely apt here!

It's been my suspicion that very few have fuel-switching on their radar, including many experts. The fact that Erik hadn’t heard of this emerging trend was supportive of my belief. While it’s been done for decades, mostly between coal and natural gas, switching into oil is a new development. This is because oil was almost always too expensive relative to coal and natural gas. Now, though, the tables have turned and oil, especially U.S. Western Texas Intermediate (WTI) at $90/barrel, is a comparative steal. (By the way, Saudi Arabia is selling oil into Asia at a $17/barrel premium to WTI.)

Erik feels the cost of converting electricity generation boilers to burn oil will prevent this from happening. However, it’s already occurring, and I’m convinced it will become one of the main ways Europe avoids severe power shortages this winter. Here’s the lead sentence in a July 11th Reuters article: “France’s energy-intensive companies are speeding up contingency plans and converting their gas boilers to run on oil as they seek to avoid a disruption in the event any further reduction in Russian gas supplies leads to power outages.”

It further quotes Florent Menegaux, a senior official at French tire goliath Michelin: “What we’ve done is we’ve converted our boilers, so they’re capable of running on gas or oil, and we can even switch to coal if we need to.” Note the past tense in his comments; i.e., it’s been done, and I have no doubt countless other large European enterprises will be doing the same, along with most of their utilities.

Another recent article estimated this might amount to a few hundred thousand barrels per day (bpd) of increased oil demand, but that sounds way too low to me. The loss of the Nord Stream 1 natural gas throughput into Germany is equivalent to about 800,000 bpd of crude on its own. It’s my belief there will be much more oil needed than that throughout Europe… assuming it can be supplied.

Source: Mike Rothman/Cornerstone Analytics

Image: Shutterstock

Thus, I’m convinced that any excess crude in either Canada or the U.S., caused by a recession-related demand drop, will be sent over to Europe in the coming months. The fact that oil is now in a bear market, having tumbled 25% from its peak right after the invasion of Ukraine, and is lower than before Putin’s tanks rumbled, strikes me as absurd. The release of 1 million bpd from the Strategic Petroleum reserve has obscured how dangerously low inventories are in the U.S. The below chart from our friends at Cornerstone Macro vividly illustrates that reality.

Source: Mike Rothman/Cornerstone Analytics

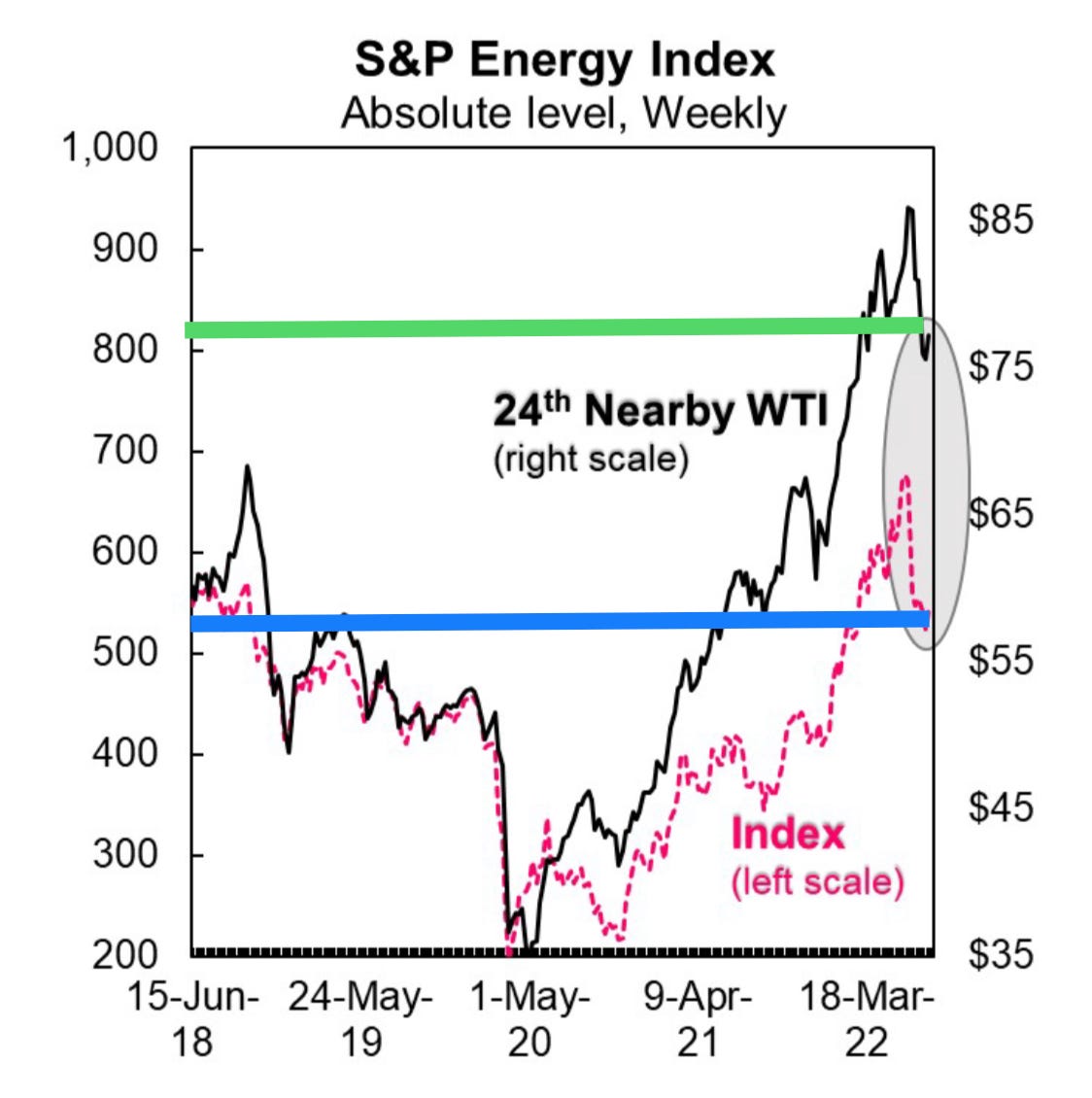

Another important point is that energy stocks are factoring in much lower oil prices than even $90. Per earlier editions of this newsletter, analysts use the futures market to create their earnings estimates for 2023 and 2024. Presently, there is about an $8 negative spread between one year out futures and current, or spot, prices. Two years out, that difference is about $16. In other words, August 2023 is around $82 and August 2024 is about $74. Accordingly, those are the prices being incorporated into energy stock valuations.

Yet, again per Cornerstone Macro, energy equities are discounting even a lower oil price, roughly $57, per the following chart. Thus, the index of energy stocks represented below at around 500 should be up in the 800 zone (left axis below), based on a two-year forward oil price in the mid 70s. That’s about 60% of potential upside. If in the summer of 2024 oil is trading well north of $100, as I believe probable, the returns should be greater yet.

Source: Mike Rothman/Cornerstone Analytics

Personally, in a world that is likely to be even more short of oil in a year or two than it is now (recession ending, China re-opening, SPR releases flipping into refills), I think buying crude at $74/barrel for delivery in August 2024, is an incredible bargain. Yet, energy equities are even more attractive. (Personally, I own both the long-dated futures contracts and am heavily overweight oil and gas shares.)

If I’m right about a high level of U.S. crude demand from foreign buyers, there should be some evidence of that — and, actually, there is. Plains All American Pipeline is one of the largest transporters of crude from America’s most prolific petroleum producing region, the monster Permian Basin. Almost half of all U.S. oil output is projected to come from the Permian this year. (By the way, shale production now represents 9 million bpd of America’s total oil output of 11.6 million bpd. What would we have done without the shale miracle?)

Plains reported its throughput was up 30% in the second quarter versus 2021. In other words, its business is booming and Jeremy Goebel, its Chief Commercial Officer said last week: “The marginal demand right now is the international (market)”. He further noted premium pricing and low inventories at its Corpus Christi, Texas export hub. It sure seems to me like the world has an insatiable appetite for U.S. crude that’s likely to become even more intense this winter.

The best investment opportunities occur when the Wall Street consensus is coming to an erroneous conclusion. Of course, that’s always a presumptuous stance to take, but the current obsession with demand destruction due to a potential recession is one of the times I feel like the odds are hugely in favor of the contrarian. The majority view is too simplistic, failing to take into account the exceptional circumstances caused by the unparalleled energy shortage in Europe and, to a lesser extent, Japan.

Unsurprisingly, the Haymaker is taking the other side of this bet. My advice is to back up the truck, load it with as much energy as you can haul, hit the gas, and swing back around next Friday for Part II.

Thanks for checking out this week’s MHM edition. Please help yourself to any of the buttons below… multiple selections encouraged.

"My advice is to back up the truck, load it with as much energy as you can haul..."

I think that's really good advice and I've been loading and am still loading the truck! Thanks David.

Excellent and thanks for defining and explaining a few key points for the non-professional investor.