Hello, Haymaker Readers:

As some of you know, Dave has spent this week and part of last enjoying a much-needed break in his (very occasional) Hawaiian getaway. To nobody’s surprise, he made time early in his trip to pen the January 16th Making Hay Monday edition, then promptly and rightly resumed vacationing (for the most part).

And because he was on family orders to take his downtime seriously, Dave agreed that this Friday would be ideal for a guest Haymaker from the Gavekal team. A piece titled Goldilocks And The Magic Money Tree by his overseas colleague, Anatole Kaletsky (which was published earlier this month), seemed to Dave like a perfect follow-up to some of his own recent missives.

Dave will also carve out time from his vacation to write a slightly abbreviated MHM for publication this coming Monday. But today, glean all you can from the famous intellect of our esteemed Gavekal guest.

Thank you from all of us.

-The Haymaker Team

To learn more about Evergreen Gavekal, where the Haymaker himself serves as Co-CIO, click below.

Goldilocks And The Magic Money Tree - Anatole Kaletsky

Originally Published: January 9th, 2023

A month ago, I wrote about the profound belief among investors, market

economists and Federal Reserve officials that the US economy would soon return to the “Goldilocks” conditions of pre-Covid, with growth neither too hot nor too cold, inflation at or very near the 2% target and interest rates lower than ever before in recorded history (see Can The Fed Make A Tough Choice?). The Santa Claus rally in both bonds and equities inspired by this belief lasted only a few days, instead of the “few months” that I had suggested.

In the second half of December, US 10-year yields jumped from 3.4% to 3.9% on evidence of strong US economic activity. And Wall Street fell sharply, with the S&P 500 down -5% and Nasdaq down -9% in just two weeks after mid-December. These setbacks were easily explained. Goldilocks hates economic overheating even more than she dislikes cold porridge, which is why we are in a “good news is bad news” market. But investors’ faith in a fairy-tale ending to the US inflation story can be revived with the slightest encouragement, like a child’s faith in Father Christmas.

Last Friday’s payrolls data revived investors’ hopes of a return to Goldilocks conditions

It took only a single line in a single data release—the (notoriously unreliable) estimate of average hourly earnings in last Friday’s US payroll data—to slam the 10-year yield back down to 3.5% and trigger a 2.5% surge on Wall Street as investors rejoiced and Bloomberg published headlines like “Fed Gets ‘Goldilocks’ in Jobs Report”. Whether this rally continues or fizzles, last Friday’s market action illustrates four market convictions that I have discussed throughout last year—and repeatedly dismissed as wishful thinking.

Four articles of faith

First and foremost, investors are more convinced than ever that US inflation is fundamentally “transitory” and will decline quickly to somewhere near the Fed’s 2% target by the end of this year, with only a few more basis points of monetary tightening. If this were not the dominant belief in bond markets, the plunge in 10-year yields to 3.5% on Friday would be impossible to explain.

If investors believed (as I do) that the US will soon face a choice between accepting permanently high inflation or a long period of much tighter monetary policy, then bond yields would move higher whichever course the Fed took: either because inflation would settle on a plateau of 4-5%, too high for bond yields to remain below 4% and the yield curve to remain steeply inverted; or because Fed policy would be much tighter for much longer than expected, raising the entire yield curve.

Bond market pricing implies one of the mildest and briefest recessions on record

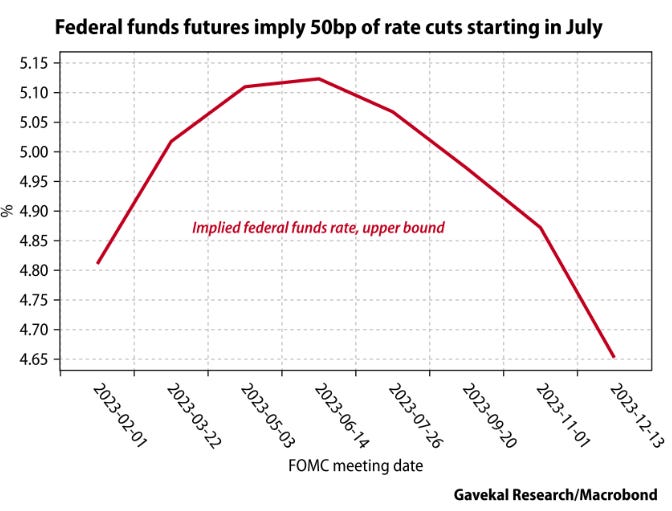

Second, investors believe (although somewhat less confidently) that a US recession has either started already or will start in the first or second quarter, but that this recession will be among the mildest and briefest on record. An immediate US recession is clearly implied by bond market pricing which shows the Federal funds rate upper bound falling from more than 5% in June to 4.65% by the end of this year (see the chart overleaf).

US policy rates are expected to fall from the middle of the year

But this recession would have to be very mild and brief to justify the robust earnings expectations and high valuations that have sustained US equities and resulted (so far) in one of the shallowest bear markets in US history.

No one on Wall Street or in Washington believes world events will disrupt US disinflation

Third, US investors are very confident that nothing that might happen outside America could disrupt the rapid and fairly painless disinflation they expect this year. Nobody on Wall Street or in Washington D. C. seems to take seriously the idea that China’s reopening in the spring of 2023 might trigger another surge in energy and commodity prices comparable to the one that followed the reopening of the US economy in the spring of 2021. Nor do they think the war in Ukraine, the exclusion of Russia from the world economy, the technology sanctions against China and the shift of the US and Europe to a wartime footing might have caused a permanent shift in global supply and demand that makes price stability impossible to restore without aggressively deflationary policies and deep recessions similar to those of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Investors expect a return to the post-GFC “new normal”

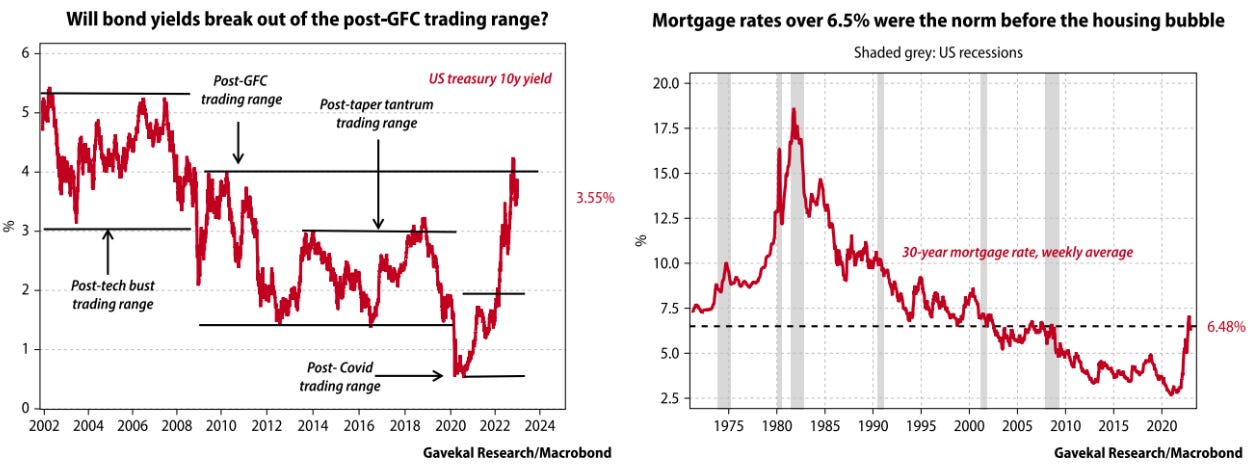

he fourth and final article of faith—and one shared by most international as well as US investors—is that, once the mild recession of 2023 is over and price stability has been restored, economic and financial conditions will return to the “new normal” that has prevailed since the global financial crisis of 2008. This belief is clearly implied by the way bond yields have retreated from their post-GFC ceilings and still remain far below their 4-5.5% trading range in the pre-GFC period, when inflation was far lower than it is today—or likely to be for the next few years (see left-hand chart overleaf).

Even more striking is the near-universal view that short term interest rates of 4% or 5% are “exceptionally high” and that US 30-year mortgage rates of 6.5% are bizarrely aberrational and completely unsustainable, even though the 30-year mortgage rate had never in history dipped below this level until the housing bubble of 2003-07 (see right-hand chart overleaf).

In the past 12 months I have devoted many papers, client meetings and webinars to questioning the first three of these assumptions—about inflation (see Five Fallacies About Inflation), recession (see Don’t Believe The US Recession Forecasts) and the irrelevance of geopolitical events (see Investors Have Forgotten That War Means Inflation).

Although the data keep moving, in my view the balance of evidence still implies that inflation will remain above 4% throughout 2023, that a recession will be avoided—at least until the fourth quarter—and that events in Russia and China will be much more important for markets than Fed policies, as they were in 2022.

If investors are right to expect a return to the conditions of 2010-19...

In the year ahead I will doubtless return to all issues, but let me conclude with an argument that is rarely made against the fourth of these “articles of faith.” This is the near-universal assumption among investors and policymakers that, regardless what happens this year, the long-term prospect for the world economy and financial markets is a return to the post-GFC conditions of 2010-19: price stability, very low interest rates and growth that is moderate but just sufficient to maintain full employment.

Reductio ad absurdum

There are many reasons to doubt this benign long-term outlook: geopolitical conflict, demographics, weak productivity, fiscal sustainability, and energy and environmental pressures. But the argument against a return to the price stability and low interest rates of the last decade that I find most convincing is a proof by reductio ad absurdum.

...the unprecedented monetary expansion of recent years has had no long-term impact

Suppose that investors are right in assuming that inflation will be brought under control by the moderate monetary tightening already implemented or in prospect and that, once price stability is restored, interest rates will return to their post-GFC levels and economic activity will resume after a relatively mild recession. This will mean that the unprecedented monetary expansion of the post-GFC decade, followed by the even more extraordinary monetary financing of government spending, borrowing and helicopter money in the Covid period, have resulted in no long-term inflationary effects and no lasting damage to economic activity or employment.

If this turns out to be true then not only were governments and central banks absolutely right to spend, borrow and print money without limit during the Covid period, but so were the economists who promoted “modern monetary theory”.

MMT holds that inflation caused by printing money can be tamed by modest tightening

MMT, parodied by orthodox economists as the “Magic Money Tree”, argued that governments should always spend whatever they need to serve the needs of society and maintain full employment, and should finance this spending by printing money, until they reach the point when inflation accelerates to an unacceptable level. Once inflation takes off, governments should tighten policy for a brief period—limiting spending, raising taxes and reversing monetary expansion—until price stability is restored. With price stability restored, governments can quickly restore full employment by spending money without limit and financing themselves through central banks.

Isn’t this exactly the conclusion that will follow if the US economy performs in the next year or two as the markets now expect? A decade of unprecedented deficits, citizen handouts and wars, financed by monetary expansion and borrowing at zero interest rates (which amount to the same thing) has resulted in a burst of high inflation.

Market expectations for the US economy imply a belief in the tenets of MMT

A moderate tightening of monetary and fiscal policies has been implemented to bring this inflation under control. This tightening will result in a mild recession and a small increase in unemployment. But with inflation declining very rapidly, policy can be eased by the middle of this year, ensuring that the recession is very brief and the economy returns quickly to full employment. Once price stability is restored, interest rates can return to near-zero and the government can spend and print money without limit to keep citizens happy and the economy at full employment.

Financial markets now assume that the US will overcome its highest inflation in 40 years with the lowest real interest rates in history. The result would be a mild and brief recession, one of the shallowest bear markets on record and no permanent damage to the economy or the labor market. In short, the people who said government could spend, borrow and print money without limit—and quickly fix any inflationary problems with a bit of policy tightening—would be completely vindicated.

If Goldilocks returns, I too will believe in fairy tales

To call the vindication of MMT a reductio ad absurdum, as I did above, is perhaps an exaggeration. MMT economists made some interesting arguments about the interaction of monetary and fiscal policy which orthodox economists and central bankers were wrong to ignore. But what about the Magic Money Tree? If inflation is cured painlessly by the end of the year and Goldilocks returns to dominate the markets for the next decade, as investors are now expecting, then governments will revive their interest in the Magic Money Tree. I too may start to believe in fairy tales—and we can all live happily ever after.

The most interesting piece I've seen this year - so far

thank you for your insights. I think understanding the future level of inflation is the number one issue today in financial markets. A big unknown in my opinion is labor availability and the cost of labor. My oldest son is 19 years old and currently starting his second certification program as a specialty welder. He recently received a job offer while still in school of $40 per hour (upon graduation - late spring 2023). It is hard to believe that a 20 year old specialty welder machist can make this much money right out of trade school. My cousin's 21 year old son recently signed on with an electrical power company outside of Tampa, Florida. He started out at $60k with benefits. I am a self-employed research biologist that works in central florida agriculture (citrus and vegetable specialist). My colleagues include local contractors, farmers, as well as multi-national life science companies that I conduct projects for. It seems that every conversation I have, the issue of available workers comes up. Nobody can hire workers. Companies are going to be very reluctant to reduce head count. Experienced workers just aren't available. I see young professionals being promoted to more senior roles at an earlier age than 20 years ago. Labor demographics have changed.