Hello, Subscribers!

Today, something a little different for you. We’re sharing some excerpted content from one of America's most popular newsletter authors, John Mauldin.

In next week's Making Hay Monday, we'll be providing some of our own macro-economic commentary and, as usual, a specific investment vehicle to, hopefully, capitalize on the likely changes coming to the Fed. Regardless of whether Donald Trump fires Jay Powell before his term as chairman ends next May, the Fed's operating model is nearly certain to be much different, and soon.

There will be winners and losers from those looming changes. We will endeavor to present to you with our best ideas on how to adjust your portfolio to the realities of a more Donald Trump-influenced (controlled?) Fed.

Of course, one of the greatest challenges the Fed faces under either Jay Powell or a less independently-minded individual, is how to finance the federal government and its massive debts and deficits. As you will read from John, this is becoming ever more daunting.

The delusion that there will be no day-of-reckoning — or, as John characterizes it — a Minsky Moment, similar to what happened in 2008, is eventually going to be shattered. In fact, John believes what's happening in the U.S. economy and financial markets currently is an "illusion of prosperity", a direct result of trillions upon trillions of government debt creation. In the Haymaker view, that's a spot-on assessment.

Of course, no one knows when the Minsky Moment will arrive but convulsions in the long-term bond market, which might be accentuated by worries about a "trained seal" Fed, may well accelerate its arrival.

(Note: You’ll also see a link to the original Mauldin post at the end of the excerpted version.)

Enjoy!

David “The Haymaker” Hay

Uncertain Moments

John Mauldin

(Originally published July 12th, 2025; abridged version below)

* * *

We like to say markets don’t lie. That may be so, but they can certainly send mixed signals.

It happened last week when President Trump announced tariff rates on several important trade partners not so different from the ones he set back in April. Back then, stocks swooned, the dollar cratered, and bond yields soared. This time, it was a big yawn. What gives?

One explanation is the “TACO” hypothesis (a term I hate because it is both derogatory and not always true), that Trump won’t actually impose these punishing rates, at least not for long. He is instead negotiating (we hope) in his characteristic way, threatening extreme consequences to get a more moderate result.

We’ll see what happens. My concern is that what Trump considers “moderate” will still be severe enough to suppress economic growth below its already-low potential. Today and over the next few weeks we are going to talk about the economic impact and cost of those tariffs. The debt situation requires raising revenue as well as spending cuts. As I demonstrated last week, we can’t simply grow our way out of this problem as we could have in the past. I think it matters how we do that.

On the market conundrum, another explanation is that investors just don’t care. Some are blissfully on autopilot, dutifully adding more to their 401(k)s every month. Others see it all as a roll of the dice. The fact that bears keep losing their shirts gives bulls more confirmation. The word for all this is “complacency,” and (to paraphrase Keynes) markets can stay complacent longer than you can bet against them. “Staying on the sidelines” while you are waiting for the end of the world which could be a long way off is not a good investment strategy.

* * *

Stability Breeds Instability

You’ve no doubt heard the phrase, “Minsky Moment.” It refers to the ideas of economist Hyman Minsky, who studied financial crises. He actually developed the main portions of his thesis in 1979 and presented them at a conference called “Reaganomics and the Stagflationary Economy.”

* * *

Minsky found crises occur when a long period of stability prevents investors from seeing risks that are, in hindsight, usually quite obvious. I have written about this before, but I think it is one of the most important things we need to understand as we think about how the future will unfold. Grasping this concept will give you a big leg up on everyone else trying to make sense of what will happen.

…And here’s the background. [I am going to insert side comments in brackets like this.]

“The phrase ‘Minsky moment’ was coined in 1998 by Paul McCulley of PIMCO fame while referring to the Asian Debt Crisis of 1997. The concept derives from the view that periods of bullish speculation, if they last long enough, will eventually lead to a crisis, and the longer the period of speculation lasts, the more severe the eventual crisis will be. Hyman Minsky worked for much of his career in relative obscurity, but that would change when his work on economic crises became unfortunately relevant. Minsky thought these events were the result of a new form of capitalism, which he called ‘money manager capitalism’ (what others would later call ‘financialization’) in the last decades before he died in 1996. Here, Minsky gives a succinct summary of his views:

‘The major flaw of our type of economy is that it is unstable. This instability is not due to external shocks or to the incompetence or ignorance of policymakers. … The dynamics of a capitalist economy which has complex, sophisticated, and evolving financial structures leads to the development of conditions conducive to incoherence—to runaway inflations or deep depressions. [JM: the general economic conditions in the US for the prior almost 200 years. Although I think he would make the same assertions today but with some nuances.] But incoherence need not be fully realized because institutions and policy can contain the thrust to instability. We can, so to speak, stabilize instability.’ [JM: which is what generally happened after 1982 as the periods between recessions and their severity lengthened.]

In one sense, Minsky was simply recognizing the reality of history. His view was dramatically confirmed by Reinhart and Rogoff’s seminal book in 2009, “This Time Is Different” which analyzed over 200 such crashes throughout world history. This is not simply an American development but seems to be part of the human experience.

Continuing the quote:

“Minsky's work describes how periods of economic stability can paradoxically lead to greater instability in the long run. According to Minsky, more investment generates higher profits at the aggregate level, all else being equal. While this is a positive sign for most investors and the public, it can make the financial system more unstable [this is Minsky’s main insight and it is a true paradox].

“When profits continually exceed expectations, servicing debt becomes easier, encouraging firms to borrow ever more sums. After all, in a booming economy, profits from speculation outpace the interest to be paid. As Janet Yellen put in 2009, ‘When optimism is high and ample funds are available for investment, investors tend to migrate from the safe hedge end of the Minsky spectrum to the risky speculative and Ponzi end.’”

* * *

… in fairness, debt isn’t inherently bad. Having it available is good if lenders and borrowers employ it wisely in productive and income-producing investments. Problems arise when they don’t.

* * *

We are right now in the late portion of the speculative finance stage. Debtors (in this case the US government) assume they’ll have the income needed or the printing press to service their debts and will be able to refinance if needed. For now, they’re right. This will change. But as I said above, governments and markets and investors can be complacent longer than you can bet against them. We are in an Era of Complacency.

* * *

Relocated Debt

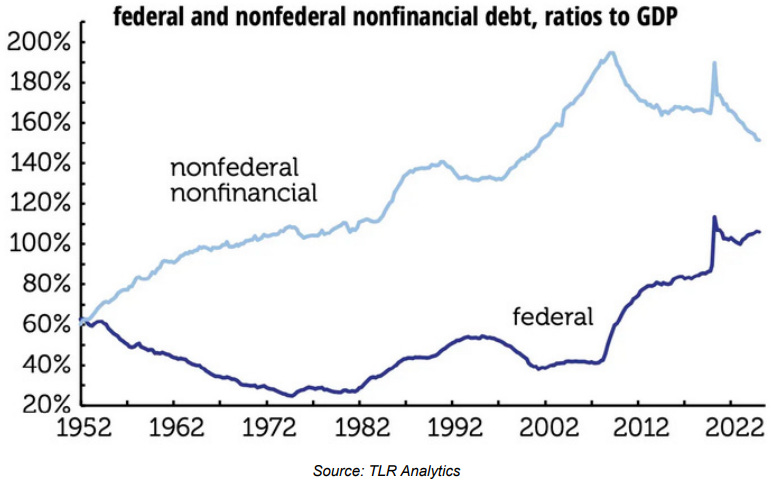

The kind of crises Minsky described happen when people become oblivious to the amount of debt they’re carrying. In the current case, this is happening in part because most people (though not all) think their own debt situations are manageable. They’re not wrong, either. My friend David Kotok recently highlighted some research by my other friends Philippa Dunne and Doug Henwood. It turns out our debt hasn’t just increased; it has also relocated. This chart shows how.

The lower, darker line is federal debt as a percentage of GDP. It fell in the 1990s and early 2000s then started rising after 2008. The other “nonfederal nonfinancial” debt represents all the economy’s other debt (except banks). Corporate bonds, mortgages, student loans, etc. It declined while government debt rose.

This chart breaks it down further. From 2008 forward, federal debt rose while the other categories fell or stayed flat (including, surprisingly, state and local government debt).

Of course, this is as a percentage of GDP. In dollar terms, debt increased across the board, but in line with economic growth—except for Uncle Sam.

What happened? My theory is that we’ve slowly transferred debts that would once have stayed in private hands to the federal government’s balance sheet, or to the quasi-federal lending agencies. The various post-2008 bailout/loan guarantee/QE programs changed the way we borrow. The assorted COVID programs changed it even more. We transferred a lot of risk from the private sector to the government.

* * *

Intentionally or not, we’ve put our debt “out of sight, out of mind.” This lets us keep merrily spending and investing in ways we probably wouldn’t if we knew how much debt we really had. The federal part is someone else’s problem… or so voters seem to think.

Falling Multipliers

Back to current events. Another reason the federal debt keeps growing is we keep expanding the federal government’s responsibilities. It does all kinds of things that were once left to the private sector, or pays for state and local governments to do them. Once in place, these expanded roles are almost impossible to reverse. More often, they just get bigger. Hence the debt.

* * *

This is the CRFB projection for how OBBBA (the Senate version, which is what finally passed) will affect the debt.

* * *

But Wait, There’s More!

This CRFB does not count “money that we owe ourselves” as part of the national debt. I understand the arguments but don’t agree with that approach. There is no Social Security trust fund. We have spent that Social Security money by using it to buy government debt. Each year we must take money from that debt “trust fund” to pay Social Security. The way we do that is to borrow more money. So while technically in a way that only a government accountant would approve, we owe it to ourselves. We are still going to have to borrow money to make those payments. And we will owe it to someone else. If you or a business have debt on your balance sheet, and have already spent the money, you cannot count it as an asset. So, to have honest accounting, let’s look at what the debt to GDP would be counting all government debt.

Thankfully, those friendly folks at the US Debt Clock have done that work for us. Quickly, here are three charts. The first one is where we are today. Note that debt is $37 trillion and is 123% of debt to GDP.

Then using their “Time Machine” feature, we can go to 2029 and see that in just four years the debt will rise to almost $47 trillion and 140% of debt to GDP.

* * *

Does anyone really think investors will want to buy US debt approaching $50 trillion for an average of 3%, let alone 2.5%? Unless it is all at Fed-manipulated short-term rates which will let inflation once again grab hold? And I would point out that inflation is just another tax and another way to pay interest. Like the old Fram oil filter mechanic used to say: “Pay me now or pay me later.”

* * *

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material has been distributed solely for informational and educational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or to participate in any trading strategy. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, adequacy, or completeness cannot be guaranteed, and David Hay makes no representation as to its accuracy, adequacy, or completeness.

The information herein is based on David Hay’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions regarding future events based on information available to David Hay on a formal and informal basis as of the date of this publication. The material may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that any opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary discussed herein will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. Actual experience may not reflect all of these opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary.

David Hay shall have no responsibility for: (i) determining that any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein is suitable for any particular reader; (ii) monitoring whether any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein continues to be suitable for any reader; or (iii) tailoring any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein to any particular reader’s investment objectives, guidelines, or restrictions. Receipt of this material does not, by itself, imply that David Hay has an advisory agreement, oral or otherwise, with any reader.

David Hay serves on the Investment Committee in his capacity as Co-Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal (“Evergreen”), registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The registration of Evergreen in no way implies a certain level of skill or expertise or that the SEC has endorsed the firm or David Hay. Investment decisions for Evergreen clients are made by the Evergreen Investment Committee. Please note that while David Hay co-manages the investment program on behalf of Evergreen clients, this publication is not affiliated with Evergreen and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Investment Committee. The information herein reflects the personal views of David Hay as a seasoned investor in the financial markets and any recommendations noted may be materially different than the investment strategies that Evergreen manages on behalf of, or recommends to, its clients.

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this material, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.