Hello, Subscribers!

In recent years, Robert Mullin, Founding Partner & CIO of Marathon Resource Advisors, has become a friend and ally of Team Haymaker; like us, he has a fondness for hard assets with favorable supply/demand dynamics. Robert shares our wariness about the excessive domination in world stock market indexes by U.S. equities. He makes the case in his Q1 2025 letter (a substantial excerpt of which we are running today) that there are signs this is changing.

As he wrote:

When a formerly 'safe' asset starts behaving in 'unsafe" ways, the logical and rational reaction is to own less of it. We believe global investors are likely to become structural sellers of U.S. assets in the years ahead as they reevaluate the optimal balance of other alternatives and return to more balanced historical weightings.

Along these lines, Robert worries that so-called U.S. exceptionalism may turn out as fleeting and erroneous as was the aura of invincibility which surrounded GE back in 2005. His comparison of its status then with the U.S. overall today is one of the more intriguing pieces we've come across lately.

One could cogently argue that the U.S. government's financial condition is actually much more precarious than GE's was 20 years ago. However, the reliance of both on short-term funding is definitely a serious risk, one that left GE in a highly vulnerable position when markets refused to rollover its debt during the Global Financial Crisis.

It seems almost unthinkable the U.S. would face that degree of investor revulsion but, as they say, stranger things have happened. The present assumption that offshore U.S. debt holders will continue to accept the risk of being repaid in debased dollars — and, now, with a threat of taxation — might trigger America's GE moment... when bad things are brought to life.

David “The Haymaker” Hay

The Transient Nature of Exceptionalism

Robert Mullin (Excerpted from his Q1 2025 Letter)

In 2005 General Electric (GE-NYSE) was the largest company in the world, an unprecedented combination of industrial might and financial sophistication. It stood at the pinnacle of the corporate hierarchy and was considered a “must own” for any portfolio manager seeking career longevity. GE produced everything from light bulbs to power stations, jet engines, X-ray machines, CT scanners, and MRI equipment. Its research division had won Nobel Prizes and introduced thousands of innovative products over a span of 120 years.

GE Capital, a sleepy corner of the business in 1980, expanded thirty-fold over the next 20 years, offering a wide range of sophisticated financial solutions to businesses around the globe. Unsurprisingly, GE was named “The World’s Most Respected Company” by the Financial Times for five consecutive years. As a result of its size and stature, financial institutions were willing to lend to GE at rock bottom rates not far above those offered to the U.S. Treasury, the world’s safest borrower. By nearly every measure, GE was the very definition of an “exceptional” company, and few could envision that ever changing.

History is rife with examples of borrowers who, once credit became excessively cheap and easily accessible, began making poor decisions, both in how much they borrowed and how they used the proceeds. While there were many factors behind GE’s eventual downfall, arguably the most damaging was its aggressive strategy of funding long-term investments with short-term borrowing. This created a severe liquidity mismatch, whereby the company’s ability to sustain its asset base became wholly reliant on the continuous issuance of short-term debt, either in the form of bonds maturing in less than 2 years or commercial paper that effectively had to be rolled every 30 to 90 days.

Such a structure left GE acutely vulnerable to the whims of its many creditors. If, for whatever reason, lenders stopped showing up, the consequences would be problematic. The GFC of 2008 proved to be exactly that kind of trigger. As credit markets seized up, GE was forced into a fire sale of assets that decimated both its balance sheet and its once-stellar reputation. Over the next 5 years, GE’s stock fell over 90%, and a decade later, the company once hailed as the world’s most respected was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average and replaced by a corner pharmacy, Walgreens.

In mid-2024, current Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent echoed the earlier criticisms of his former boss, legendary hedge fund manager Stanley Druckenmiller, directed at the then- Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen. Their concerns centered on the growing reliance on issuing short-dated bills and bonds, both to roll the $7 trillion of debt maturing in 2025 and to fund what now appear to be structural deficits of $1-$2 trillion annually. Yet, just 4 months into his tenure, Bessent now oversees a Treasury Department that is doing almost exactly the same thing.

We believe this is not Secretary Bessent’s preferred course of action, but rather the only path that markets will currently allow. More specifically, the global investors on whom the U.S. increasingly relies to fund its spending are unwilling to lend at the prevailing rates offered on 10- to 30-year debt. Historically, the most eager buyers of such long-dated securities have been companies and countries with trade surpluses with the U.S., or ones that viewed U.S. assets as anti-fragile and/or strategically essential. As outlined above, both pools of these buyer bases may now be shrinking.

In our view, the foreign appetite for U.S. assets may be at or near its crescendo. It would take very little to begin to reverse those flows, and the recent wave of trade assaults, directed at friends and foes alike may well be enough to do the trick.

Our current macro outlook incorporates a broad range of potential financial market outcomes. When we put on our “rose colored glasses,” we can imagine a scenario of a rapid and simultaneous “threading of the needle” on tariffs, multiple global armed conflicts, and an increasingly uncertain economic and corporate earnings backdrop. This (unlikely) alignment could re-ignite animal spirits and trigger the liquidity flows necessary to sustain both the stretched valuations of U.S. equity markets and the massive tsunami of ~$9 trillion (25% of U.S. GDP) in debt issuance expected over the coming year at semi-reasonable rates.

Through deft manipulation of the Supplemental Leverage Ratio (SLR) to expand bank balance sheets and aggressive tariff-negotiation arm twisting to coerce foreign buyers into supporting the Treasury market, policymakers might blunt, or even offset, a broader rebalancing away from U.S. government debt. That said, with U.S. equities currently trading in the most expensive 2% of historical valuations and at a record spread relative to non-U.S. equities, it’s fair to say that much of this ‘best-case’ scenario is already priced in.

What if, instead, the U.S. is the modern-day equivalent of General Electric, universally lauded and richly valued, now abusing its abundant access to capital and increasingly reliant on the continued generosity of creditors to fund an unsustainable spending habit? While most would consider any suggestion of declining U.S. exceptionalism to be heresy, we see both the warning signs and potential catalysts for a dramatic reversal of fortune.

If we allow ourselves to indulge our deepest concerns, we can envision a greatly destructive and violent unwinding of the last 20 years of U.S. outperformance. In such a scenario, prolonged geopolitical uncertainty and its accompanying economic fragility could steadily erode the global appetite to keep placing much of their capital in U.S. assets. The shift could trigger a sharp decline in U.S. equities and a corresponding rise in U.S. interest rates, an outcome with severe consequences for America’s hyper-financialized economy (h/t Julian Brigden), where falling asset prices precipitate rising unemployment. The combination of foreign investors becoming net sellers of U.S. assets and a slowdown of 401(k) inflows into the S&P 500 has the potential to slow, or even reverse, the Pavlovian passive inflows (h/t Mike Green) which have underpinned elevated U.S. valuations. This pivot from “buy everything regardless of valuation as long as money is coming in” to “sell everything regardless of valuation when money is flowing out” would likely prove distinctly unpleasant for most of existing asset allocations.

Taking a step back, we believe it’s essential to recognize that the world has been living through an extraordinary period of outsized U.S. returns, one that is highly unusual and historically unsustainable over longer periods. Rarely do such outliers persist beyond 10-15 years; more often, they are followed by extended periods of low or even negative real returns. Statistically, the most probable path for future financial returns likely lies somewhere between the optimistic and pessimistic outcomes we’ve outlined. The key question for investors is not which path is right, but rather, how likely is each, and how best to position portfolios for that distribution.

Our friend and recently retired CIO of Evergreen Gavekal, David Hay, whose market views often align closely with our own, recently captured the implications of the current political and economic backdrop more succinctly and eloquently than we ever could in a recent post on his indispensable blog, The Haymaker:

Investment Implications

Hard assets matter again.

If sanctions can’t halt tanks and GDP can’t measure resolve, then resource-rich nations and commodity-linked businesses may carry more strategic weight — and more pricing power — than the market currently acknowledges. This favors energy producers, defense contractors, and firms with exposure to scarce materials (especially outside the G7 orbit).The “exorbitant privilege” is not infinite.

The dollar may remain dominant, but it’s no longer unchallenged. Watch moves by BRICS+ nations, energy trade settled in yuan, and any shift in reserve allocation behavior. Over time, this could favor gold, select foreign equities, and alternative monetary anchors — not in a panic, but as a quiet repositioning.Expect more policy volatility.

In a world where economic orthodoxy takes a backseat to geopolitical necessity, don’t be surprised by inconsistent rate moves, politically driven stimulus, or fiscal actions that defy standard playbooks. That likely means higher volatility, a steeper risk curve, and more frequent regime shifts — a tailwind for global macro and long-vol strategies.Rethink your safe havens.

Sovereign debt of highly indebted nations — once a ballast in portfolios — now comes with directional risk. Consider whether assets like short-duration Treasuries, commodity producers, or cash-flowing infrastructure businesses might serve as better anchors.

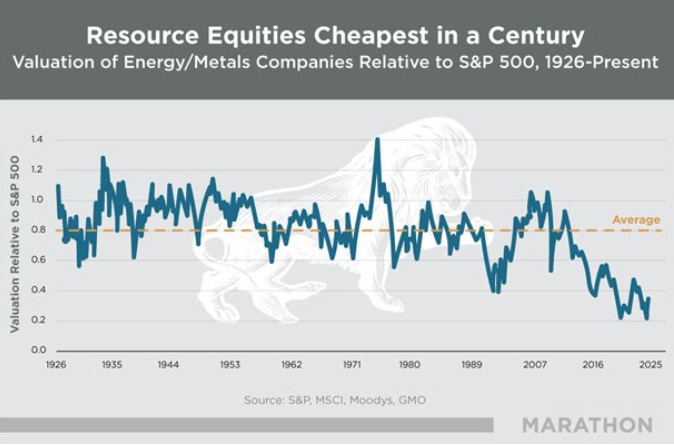

We believe RAIEF is uniquely well-suited to the current macroeconomic backdrop and geopolitical environment. As an active manager of capital, we continue to broaden the strategy’s exposure to high quality natural resource equities that are trading at historically steep valuation discounts relative to the broader market and whose representation in major stock indices have been divested to 50+ year lows. This blueprint remains highly attractive even if the eventual outcome is nothing more than a modest reversion to the mean. Given how deeply out of favor these stocks are today, a return to “average” could yield multi-fold appreciation.

* * *

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

This material has been distributed solely for informational and educational purposes only and is not a solicitation or an offer to buy any security or to participate in any trading strategy. All material presented is compiled from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy, adequacy, or completeness cannot be guaranteed, and David Hay makes no representation as to its accuracy, adequacy, or completeness.

The information herein is based on David Hay’s beliefs, as well as certain assumptions regarding future events based on information available to David Hay on a formal and informal basis as of the date of this publication. The material may include projections or other forward-looking statements regarding future events, targets or expectations. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee that any opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary discussed herein will be realized or that an investment strategy will be successful. Actual experience may not reflect all of these opinions, forecasts, projections, risk assumptions, or commentary.

David Hay shall have no responsibility for: (i) determining that any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein is suitable for any particular reader; (ii) monitoring whether any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein continues to be suitable for any reader; or (iii) tailoring any opinion, forecast, projection, risk assumption, or commentary discussed herein to any particular reader’s investment objectives, guidelines, or restrictions. Receipt of this material does not, by itself, imply that David Hay has an advisory agreement, oral or otherwise, with any reader.

David Hay serves on the Investment Committee in his capacity as Co-Chief Investment Officer of Evergreen Gavekal (“Evergreen”), registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission as an investment adviser under the Investment Advisers Act of 1940. The registration of Evergreen in no way implies a certain level of skill or expertise or that the SEC has endorsed the firm or David Hay. Investment decisions for Evergreen clients are made by the Evergreen Investment Committee. Please note that while David Hay co-manages the investment program on behalf of Evergreen clients, this publication is not affiliated with Evergreen and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Investment Committee. The information herein reflects the personal views of David Hay as a seasoned investor in the financial markets and any recommendations noted may be materially different than the investment strategies that Evergreen manages on behalf of, or recommends to, its clients.

Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that the future performance of any specific investment, investment strategy, or product made reference to directly or indirectly in this material, will be profitable, equal any corresponding indicated performance level(s), or be suitable for your portfolio. Due to rapidly changing market conditions and the complexity of investment decisions, supplemental information and other sources may be required to make informed investment decisions based on your individual investment objectives and suitability specifications. All expressions of opinions are subject to change without notice. Investors should seek financial advice regarding the appropriateness of investing in any security or investment strategy discussed in this presentation.