Crude Calculations

In The Ring - April 15th, 2022

Fundraising Note & Making Hay:

Before beginning this inaugural Haymaker, we are overjoyed to announce that with the generous support of so many of our friends, partners, clients, and readers, we have met our $100,000 Ukraine Relief fundraising goal. This effort was facilitated via our partnership with the Salvation Army, a group whose work in and around Ukraine since the crisis took root has been extraordinary. We have no doubt the money we raised through our wonderful network of giving souls will be applied to undeniably humanitarian and unfortunately necessary efforts throughout the coming weeks and months. Our thanks to you.

—

Making Hay is a seamless continuation of my weekly Positioning Recommendations newsletter, an EVA mainstay that will live on here at Substack as a sub-brand of Haymaker. In it, you will find research-heavy analyses of current market conditions, along with clearly stated opinions as to how your portfolio should be, yes, positioned in response to said conditions.

This long-running project amounts to a major pillar of the advisory value I bring to my clients. Under the Making Hay banner, that project will carry on.

-David Hay

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” - Mark Twain

Oil is rather an important commodity. Though roundly despised in many circles, modern life can’t go on without it, a reality that incenses much of the intelligentsia. What is happening in Europe today is such an obvious example of this inarguable fact, that I’m almost embarrassed to bring it up… almost.

I believe the essential nature of oil—and its related high-energy-density fossil fuel, natural gas—is poised to become, frankly, even more underscored in the months ahead. Few seem to realize the critical role played by fossil fuels when it comes to food production.

With the Russo-Ukraine conflict still raging, the 25% of world wheat supply that comes from that region will undoubtedly be diminished, after which fuel’s part in the agricultural equation will be made painfully apparent. Lower crop yields are also virtually a given as fertilizer prices, which are going postal, lead to farmers worldwide expending far fewer chemical nutrients.

The irony of policymaker attitudes toward fossil fuel energy is bad enough, until you consider the hypocrisy. They beg for increased production while thinly disguising their belief that it’s a dying industry. A critical trans-governmental organization, the topic of this EVA, is a classic example of this cognitive dissonance.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) is the planet’s authority on pretty much all things related to global energy production and consumption. However, its main focus is on oil. So, imagine the energy industry’s reaction last summer when the IEA suggested a steep reduction in oil exploration activities — in this case, the agency’s translation of “reduction” is “complete suspension by the year 2022.” Yes, that would be as of this year. After all, how else could the 2050 goal of net-zero carbon emissions be achieved? (A realist cynic might postulate that there is zero chance of net zero by 2050 — barring a nuclear power breakthrough, such as with molten salt reactors, a highly promising technology.)

This furnished the IEA with a “Don’t shoot the bureaucratic messenger” excuse. However, letting it off the hook on this basis would be granting a far too easy pass after years of misinformation that borders on deception. They’re so slick, they should consider going into the oil busin… oh, wait.

With organizational gravitas that exceeds its actual value, most global government agencies and private sector participants, including institutional investors, heavily rely on IEA data. As Bloomberg reporters Alex Longley and Julian Lee wrote in a January 20, 2022 article: “Its monthly report is a benchmark for traders trying to evaluate the balance between supply and demand the world over.” Accordingly, the accuracy of its oil market findings is far from trivial — more like the photographic negative thereof.

Another polar opposite situation occurred on February 11th of this year, when the IEA announced revisions to its assessment of the oil market’s supply and demand status going back to 2007, with the biggest relating to 2014 onward. Unlike with its widely-publicized proclamation that the development of new oil (and gas) resources should be almost immediately halted, the 2/11/2022 recalculations received scant press coverage. One might assume that was because said revisions were minor. If so, one would not only be wrong but very wrong.

For elaboration, let’s turn to Cornerstone Analytics, a justifiably pricey energy research service to which I have subscribed for years. Cornerstone’s founder and primary oil market diviner is Mike Rothman, who has been in a vigorous opinion exchange with the IEA for nearly a decade. Mike has been the primary advocate of the concept that he somewhat facetiously refers to as the mystery of the “missing barrels”. In his words: “While most believed the volumes of these missing barrels were on tankers circling the globe somehow ready to come to port, the fact is the ‘missing oil’ never shows up, never. In almost 40 years of covering the global market, there’s not a single instance of those unaccounted supplies showing up. The issues are always resolved by the IEA revising up its demand series.”

So, how much was the IEA’s February adjustment? “Only” 2 billion barrels going back to 2014 due to chronically underestimated demand. Another 340 million barrels were a function of overcounted supply.

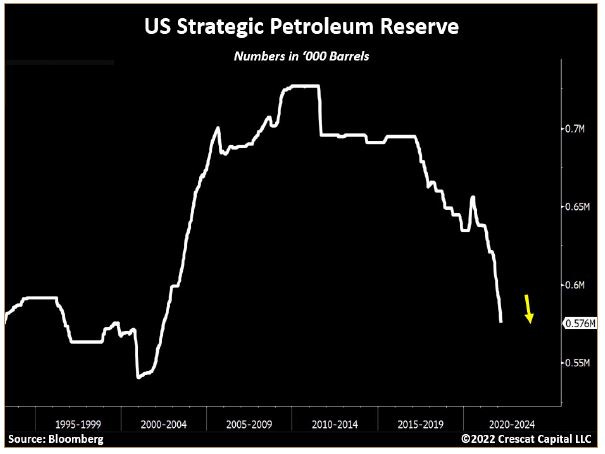

Despite this gargantuan revision, the largest in the IEA’s nearly 50-year existence, another 700 million barrels remain MIA, for a combined total (1.7 billion plus 340 million plus 700 million) of 2.7 billion barrels of phantom petroleum. The entire U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve, for context, is around 570 million barrels. That number will quickly drop with the Biden administration’s pledge to release 1 million barrels per day (bpd) starting in May and — I’m sure, totally coincidentally — ending in November. This is the third SPR release in recent months and will draw it down to less than 400 million barrels by the time the mid-term elections have occurred.

As far back as the 1990s, the IEA was sued, and lost, for a similar statistical error, though of a much smaller magnitude. Mike Rothman was one of the primary sleuths who unveiled their error at the time. Lesson learned? Certainly not. Here’s how it’s doing so far this year:

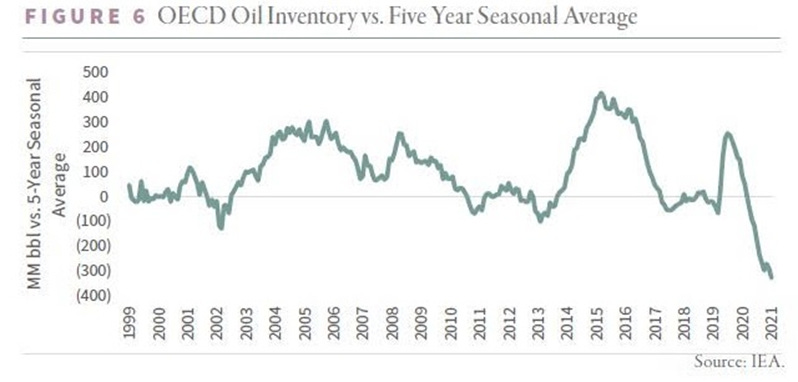

“NA” stands for “North America”, “Pacific” represents Australia, New Zealand, South Korea and Japan (notably excluding China). Combined, they account for 70% of global oil inventories (again excluding China; Mike does a special calculation to estimate their crude stocks). Therefore, as goes NA and Pacific, so goes most of the planet. How the IEA has any credibility left is an enigma right up there with why anyone listens to the Fed’s economic forecasts.

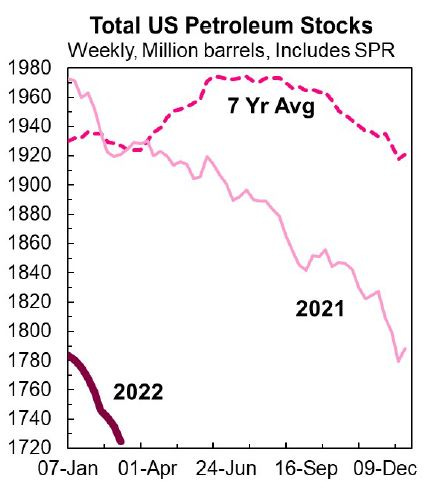

Massive oil inventory drawdowns, occurring since the spring of 2020, and which the IEA has grossly underreported – resulted in both U.S. and overall developed world oil stocks being shockingly low. As they sort of say, a couple of charts are worth 1000 words (if only they were worth 1000 barrels - we could use them).

These dangerously low inventory readings preceded the loss of Russian oil due to international sanctions. Setting aside the official restrictions, Russia’s crude exports are becoming radioactive (metaphorically only, God willing) with tankers reluctant to ship it, just as insurers are unwilling to provide coverage. Plain as the reality is, the IEA is forced to acknowledge, and now estimates supply losses of 2 to 3 million bpd. Over an extended period, even a 1 million bpd deficiency is a big problem. Presuming a new world disorder where Europe, in particular, is exceedingly reluctant to rely on Russian oil and/or natural gas, this problem isn’t going away anytime soon.

Unfortunately, for the interests of preparedness, the IEA’s inexcusably sloppy accounting largely obscured the severity of the pre-war shortage. Given the Russian situation, which some more credible experts than the IEA estimate could remove 4 million barrel per day of supply, it is poised to become catastrophic.

But wait, there’s more!

On Monday, April 4th, I read the opinion of one of the financial industry’s most respected economists who also offers financial predictions (though he has badly missed the inflation eruption and the bond market carnage). He mused that oil could soon by back down to the $70 level. With commodity prices, including crude, anything is possible, but I doubt this individual is aware that things aren’t exactly ducky in America’s Permian Basin, our country’s most prolific oil and gas producing region.

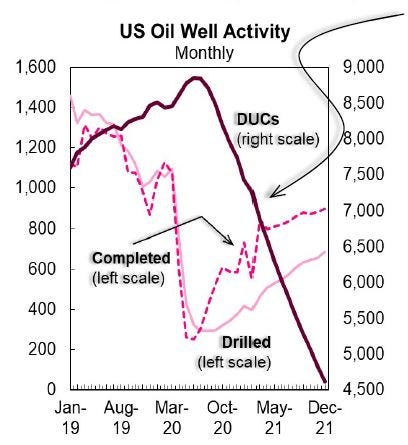

DUCs is oil industry shorthand for “Drilled but Uncompleted” wells, a sizable backlog of which accumulated during Covid as completion activity crashed. This phase is when the fracking process kicks in and in the spring of 2020 it ground to almost a total halt (as did drilling). But over the last nearly two years, completions have soared, allowing U.S. production to bounce back. Moreover, it’s been able to happen with a much lower level of drilling than would normally have been required to achieve this output recovery. Yet, as you can see, DUCs have performed a nosedive worthy of a meme stock. Industry experts believe they are about as low as they can go.

The oil industry, like the industrial sector, is afflicted with significant shortages in terms of labor and materials. As a result, a heroic drilling ramp-up is going to be exceedingly difficult to accomplish. Even if, miraculously, drilling surges, the completion process is now also coping with extreme deficits, particularly of sand, which is essential to fracking for oil and gas.

How can there be a shortage of sand in West Texas, where the Permian is located (it extends into New Mexico)? There probably isn’t, but fracking requires a very special type of sand (yes, there are grades). Frac-quality sand is in such short supply right now that making up for the lack of in-basin supply means importing it from just up the road… as in, Wisconsin… via railway, an extremely costly (dare we say, energy-intensive) solution.

And with so many other distractions, few Americans are aware of shale’s precipitous decline rate. Instead of the usual 4% to 5% taper of traditional producing reservoirs, shale wells plunge at a 40% annual rate in their first two years of life, leaving a minor amount of future production. With shale now representing around 7 ½ million bpd of America’s oil output, it means roughly 3 million bpd of new oil needs to be brought to market merely to stay steady-state!

Considering current equipment and personnel obstacles, even the ultra-resourceful Permian producers are hard-pressed to maintain, much less grow, output. In my opinion — and I personally know some of the best and brightest— they can do it; but I still don’t see the U.S. getting back to its pre-Covid 13 million bpd anytime soon. (Total global oil supply is roughly 100 million bpd.)

Considering the dangerously low level of crude inventories, the near certain loss of millions of bpd of Russian oil, and even the most prolific oil producing basin in the U.S. facing an uphill climb almost worthy of Sisyphus to increase output, I couldn’t disagree more with the $70 oil price number posited by the above-referenced esteemed economist. Crude might have “70” in its price tag this year, but, if so, I believe it will have a “1” in front of it.

I can't tell you how much I enjoyed Bubble3.0 and your ongoing commentary. As I age and time becomes an even more precious commodity, I never worry about wasting time when I read what you've been pondering. Bottom line: thanks for your diligence, it does not go unappreciated. By the way, it took courage to end Bubble with a pun...my college buddies I go fly fishing with gave me a T shirt I wear proudly knowing my love of puns. It reads "Bad puns, It's how Eye Roll".

Would you start a new well in this environment? Today, the folks I know in Midland, TX are content to keep the number of their wells low. Maybe, maybe they'll start drilling with a few more rigs. But they never know when a Biden flunky will show up, shut down a pipeline, and then they are left holding a bag of oil they cannot transport.

So the cure for high prices is no longer high prices - but an administration willing to let you drill in a sane atmosphere that will cure high prices...